We have the medical clearances; we have the forms from RUB. Except we’re missing a form: a request from the Ministry of Labour and Human Resources. Young Ugyen Wangchuk has only been in the job a few weeks. First, he can’t find the forms. (“People take things and don’t bring them back,” he mutters, leafing through a folder that seems to be organized by date of receipt, which would defeat any effort of mine to find anything.) An older woman passing on the stairs asks whether he’s made a call. “Not yet,” he says. “I was busy all weekend with His Majesty’s visit.” Then he starts going through email on the computer. Thank goodness for a digital record.

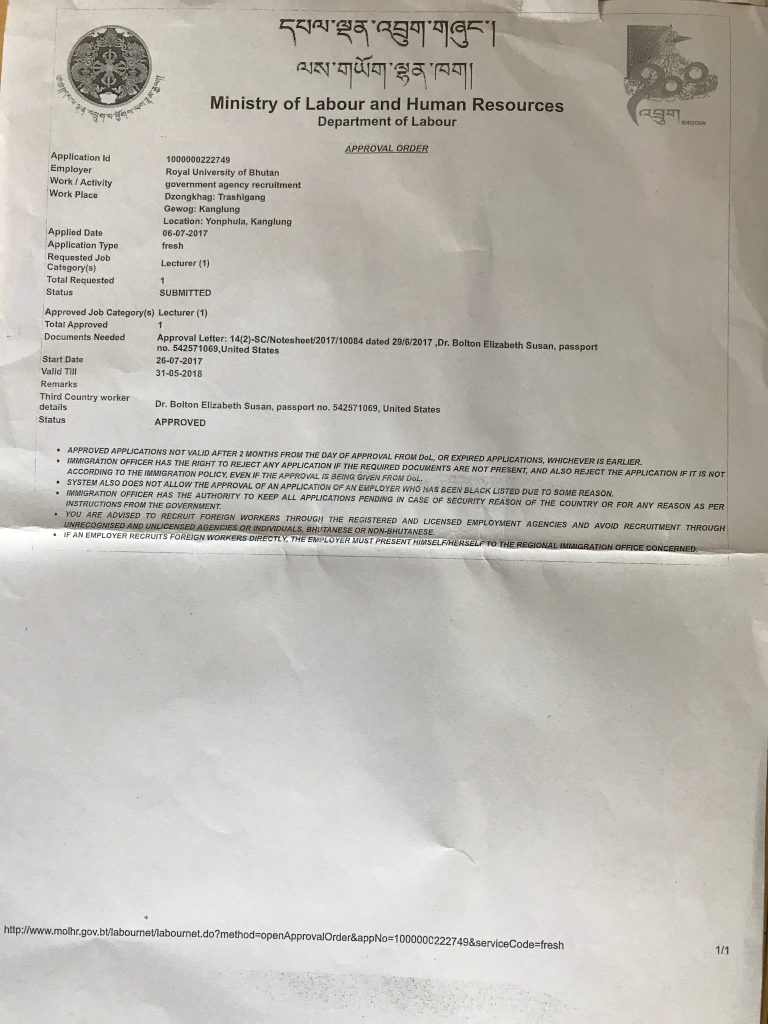

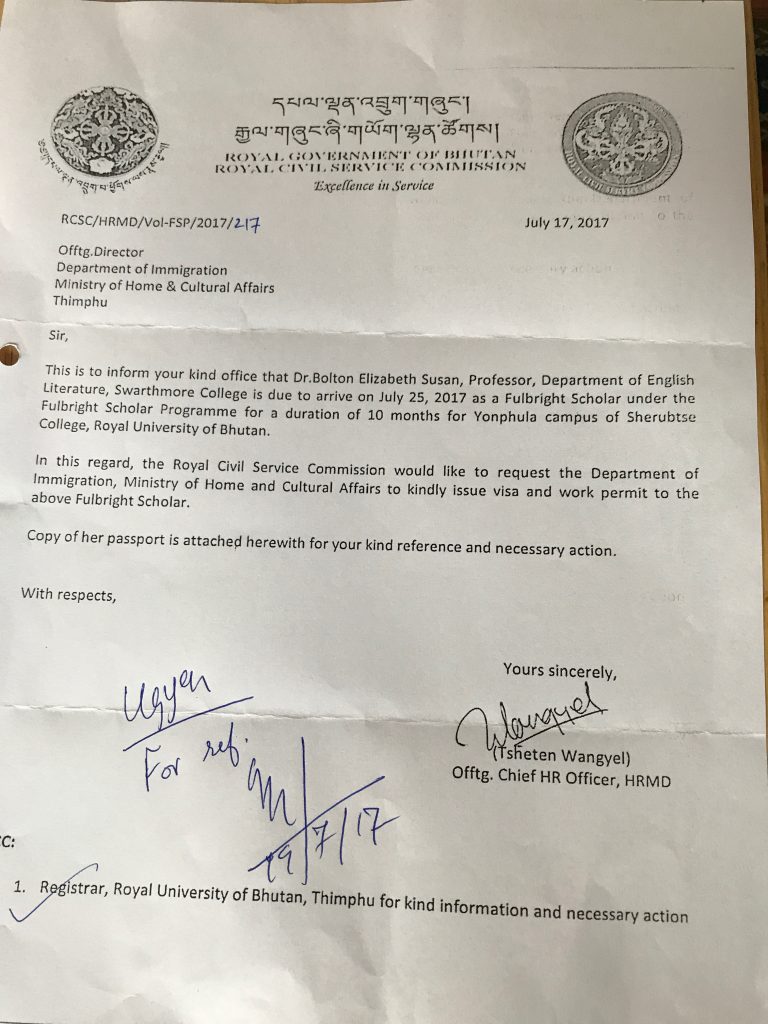

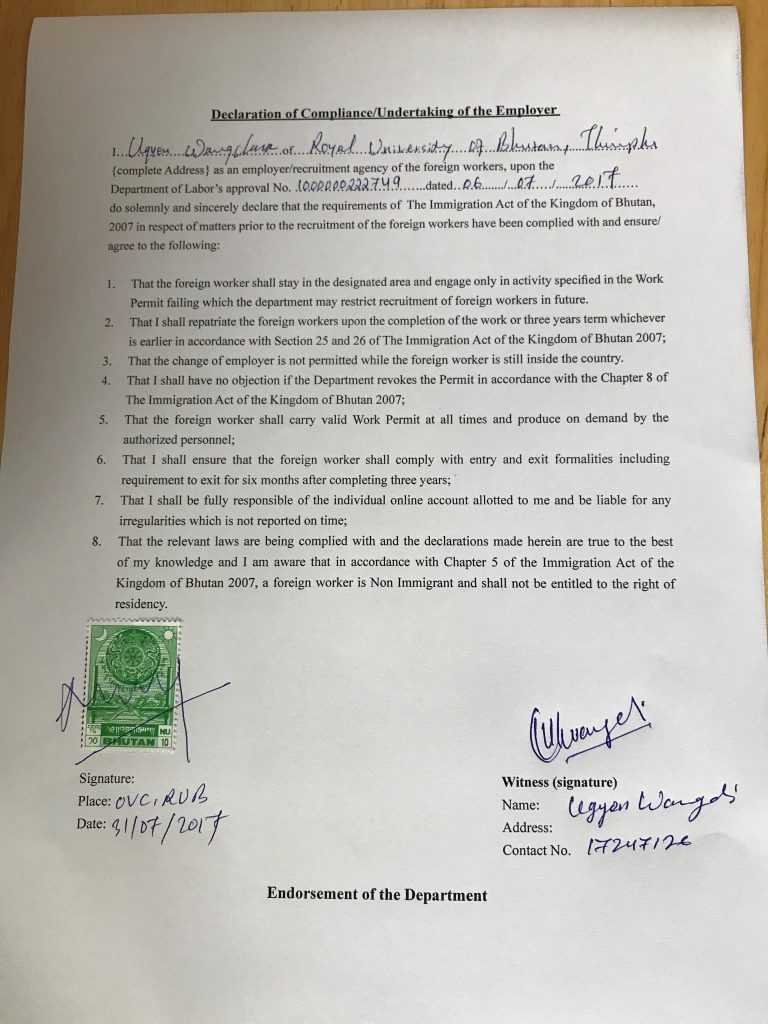

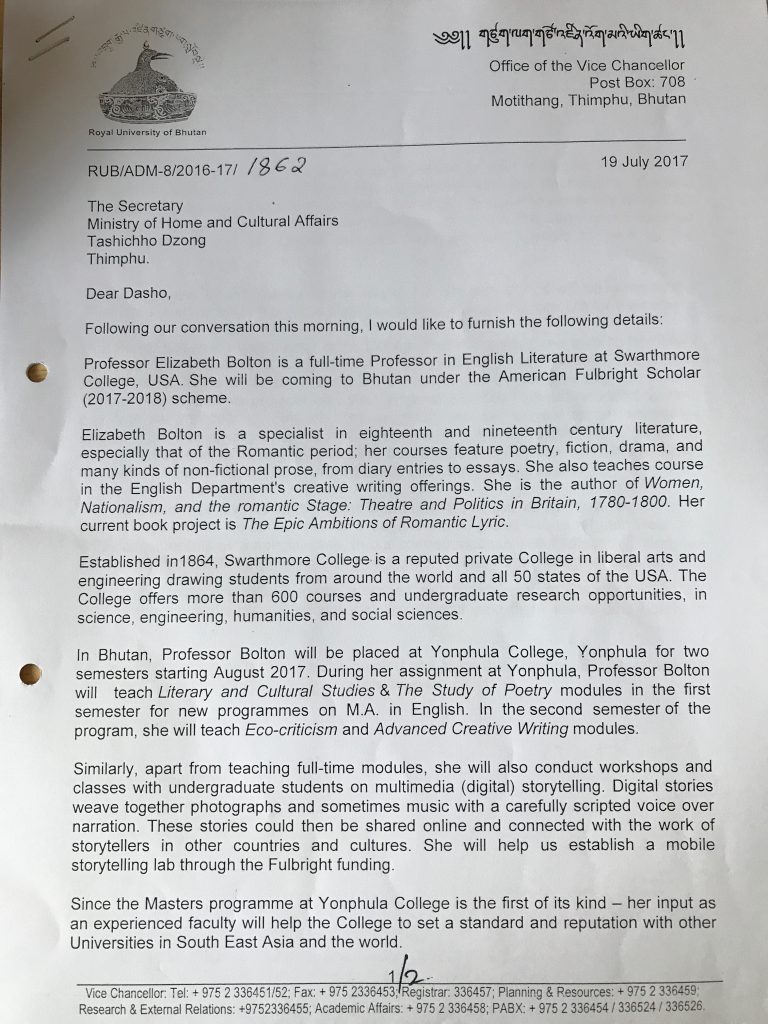

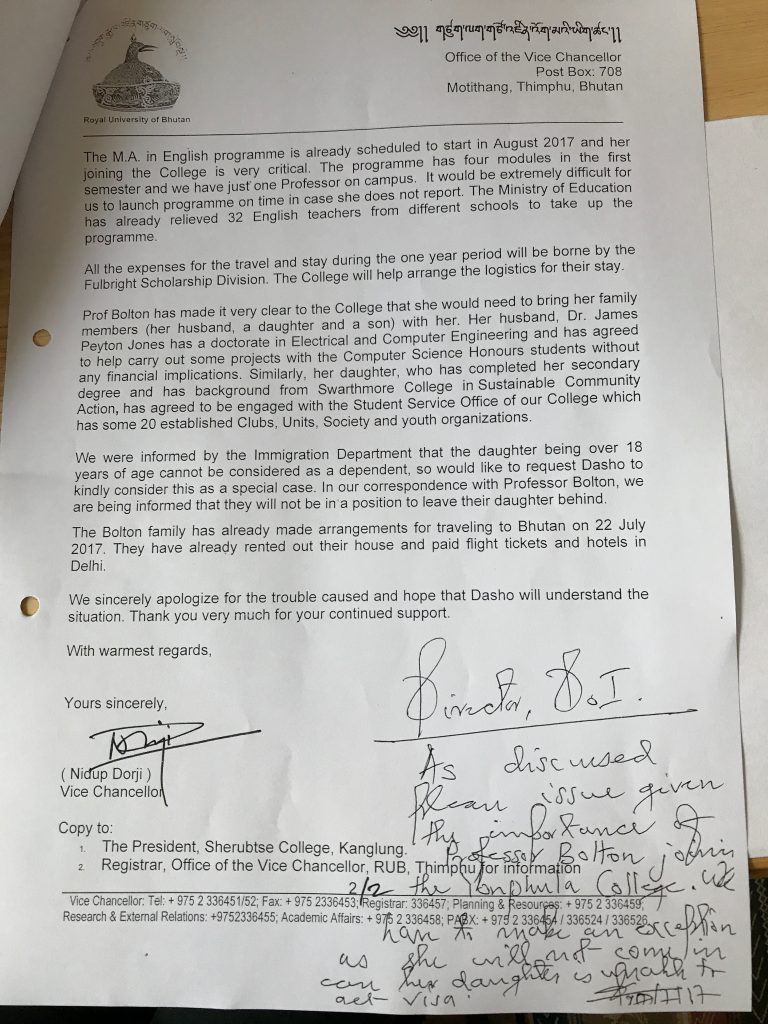

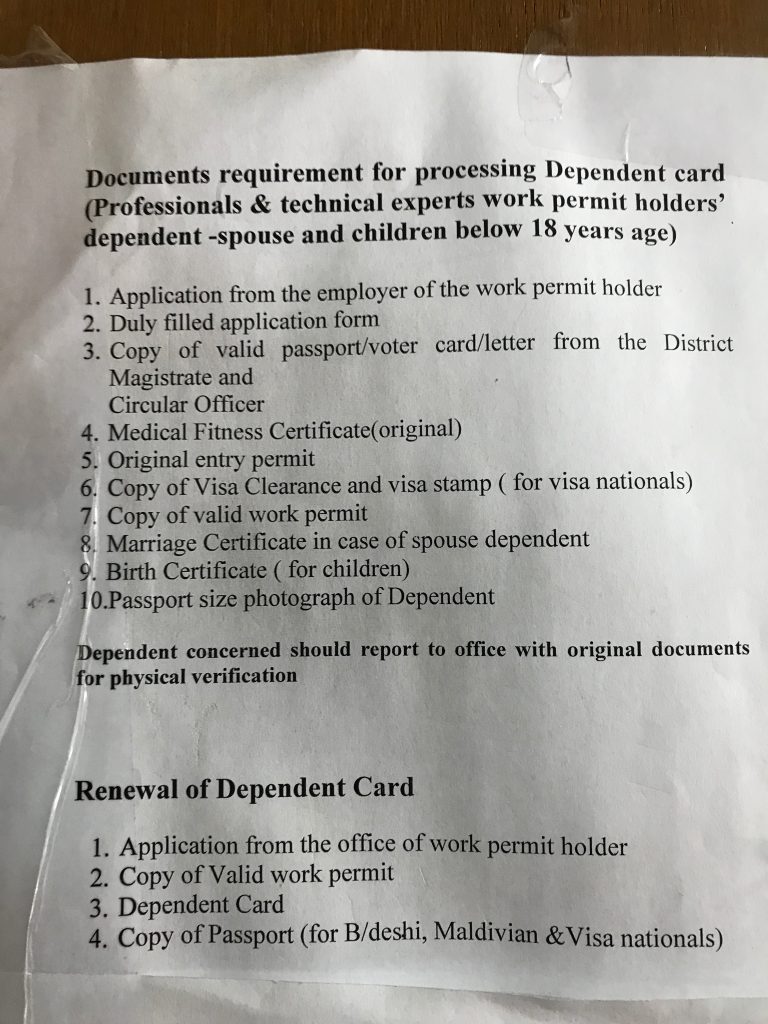

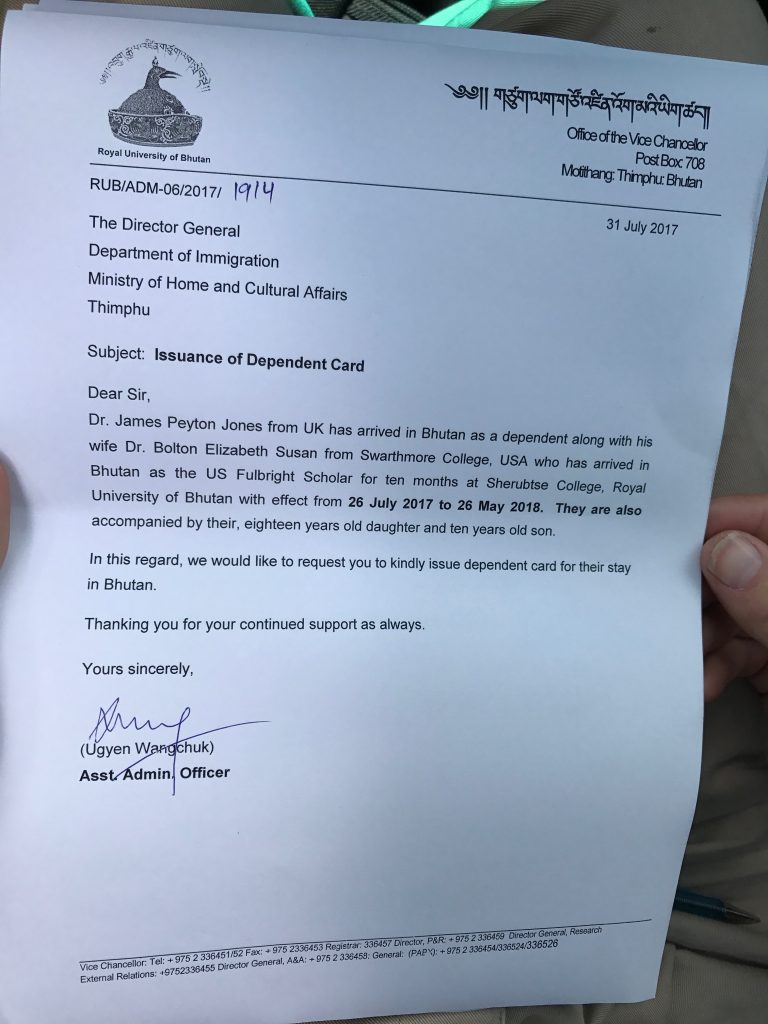

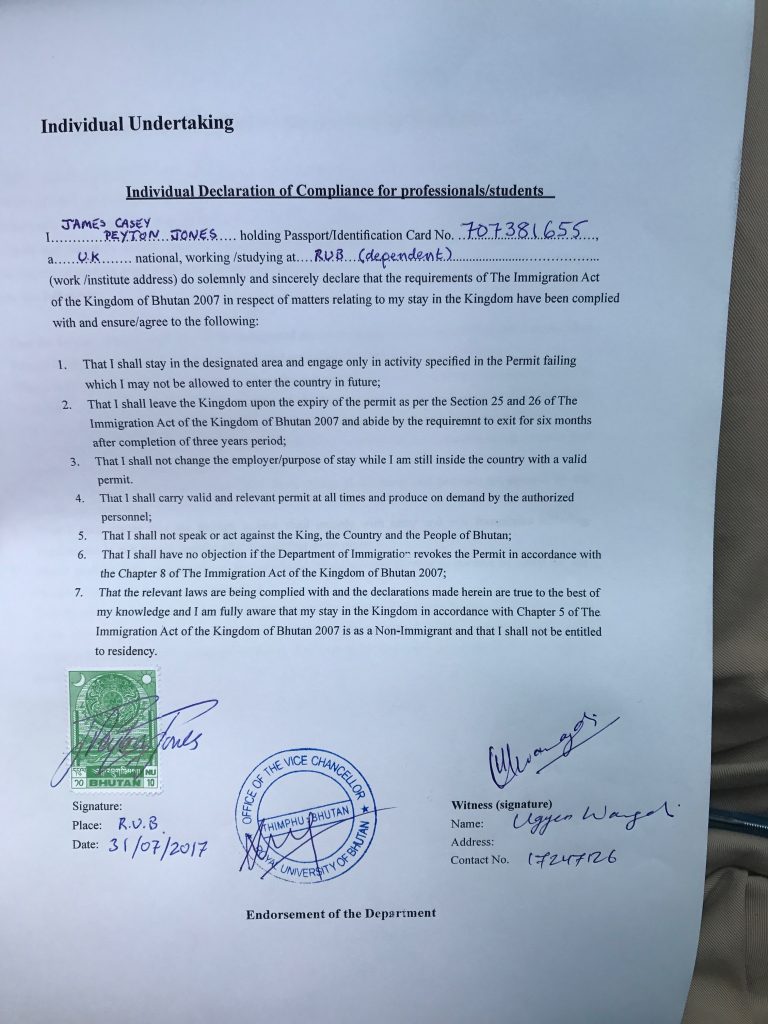

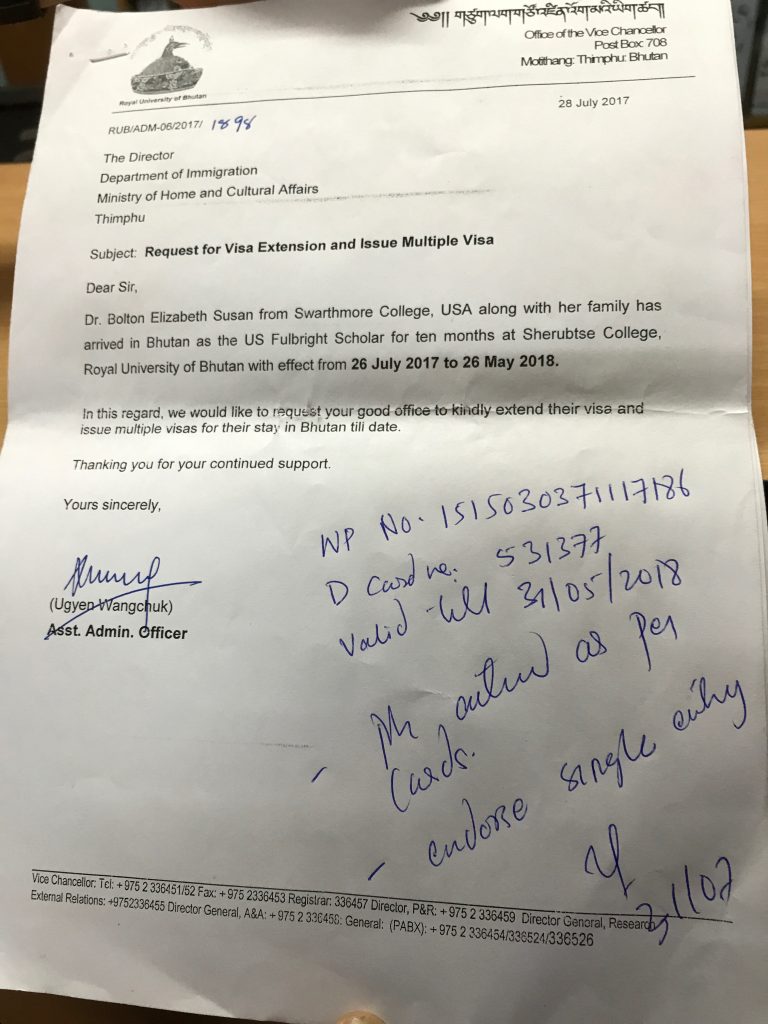

Here are some of the forms signed and countersigned in pursuit of a work visa (I didn’t manage to take photos of all the forms):

I’m intrigued by the residual history marked by the required vow not to speak against the Immigration Act (there’s a personal version of this same form that I had to sign, so both the sponsoring organization and the visa grantee have to make this commitment).

Once I’m through, we move onto the question of dependents. James needs a dependent card, and of course, we get to go around the question of Zoë’s visa a second time. We go from the Immigration office to RUB for what seems like the umpteenth time. It turns out that what we need is a handwritten note from the Home Minister in reply to a letter from the Vice Chancellor.

“As discussed please issue given the importance of Professor Bolton joining the Yonphula College. We have to make an exception as she will not come in case her daughter is unable to act [sic] visa.”

We carry that handwritten note down to the Immigration Office. James has to come in and have his photo taken. Then we have to pay for the visas and for entry permits.

“The visa applications specify multiple entry visas,” the head officer explains. “But that’s quite expensive: 24,000 ngultrum per person.” Given that we can only take out 10,000 ngultrum at a time (and that’s $150, we decide to stick with a single entry permit for the moment. Off we go to a cash machine, then to a different desk to make the payment and get a receipt, then back to the head officer, then out to a different counter for the actual visa stamps.

“The visa applications specify multiple entry visas,” the head officer explains. “But that’s quite expensive: 24,000 ngultrum per person.” Given that we can only take out 10,000 ngultrum at a time (and that’s $150, we decide to stick with a single entry permit for the moment. Off we go to a cash machine, then to a different desk to make the payment and get a receipt, then back to the head officer, then out to a different counter for the actual visa stamps.

If we decide to add entry permits (which we will have to do), then we have to find out how to do this through the central office so that there is an up-to-date record. In the meantime, the single-entry permit determines our path for the trip to Kanglung: we will take the Bumthang road and hope for decent road conditions. Going through India would burn through our one entry permit.

By the time we have our work permit, dependent card, and visas in hand, it is too late to reach Bumthang before nightfall. “Hurray!” says Jeremy. Time for lunch at Ambient. Jigme is there: after some conversation, he and Jeremy start watching Wonder Woman. Both Jigme and his dad are wearing the Bhutanese version of “Meatless Monday” tshirts. James and I end up chatting over lunch with Hendrik Visser, a Dutch man who has started the first residential care facility for dogs in Bhutan. He and his partner have treated dogs associated with the royal family and other high-level personages, which is how they have remained in Bhutan for 16 years, despite the fact that they draw attention to problems others might wish to ignore. He gives us his card in case we see a dog in need in Kanglung. “There are always people traveling west: you could have them bring such a dog to us.”

We try to visit the painting school, but it is closed for the afternoon. We do succeed in visiting the heritage museum, where photos are permitted outside but not inside. (With a work permit, we are locals for the purposes of museum entry, which means we pay 10 ngultrum instead of 200.)

The construction of walls is broken down into bamboo and earthen plaster construction;

external walls made of pounded earth are also represented here.

I think this is a space designed to burn incense.

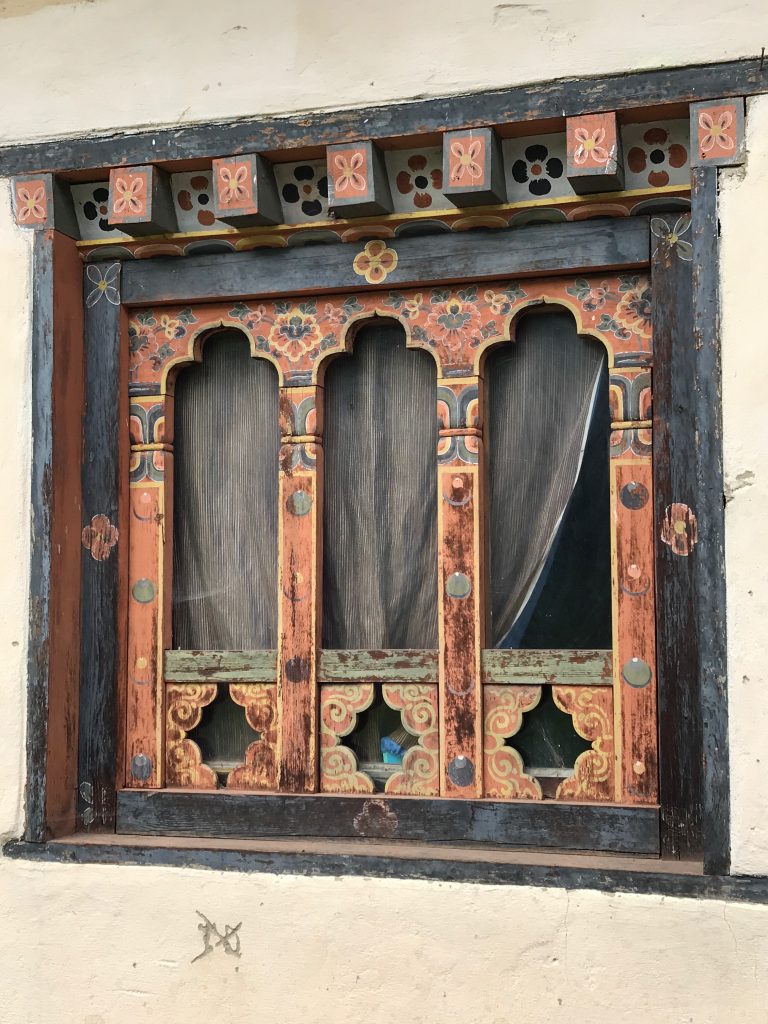

The building itself was fascinating: the ground floor would have served as a stable for cattle and other animals. Dried leaves would be used as bedding: combined with manure, those leaves would become compost for the fields. The first floor served as a kind of storeroom, with enormous pots to hold rice or other goods. Weaving materials were kept in a side room of this first floor. With shutters closed, the space was very dark. The second floor (third floor in American terms) was divided into 1) a kitchen with a massive hearth (most of the family would sleep here, near the fire; 2) a spacious but largely empty room; and 3) an altar room, with thangkas and a large, ornate piece of furniture holding offering bowls and other religious objects. Here is a version of that kind of furniture, this version made by Ugyen Wangdi’s father and installed in the Director’s office at Yonphula.

Off this altar room was a smaller “throne room” in the modern slang sense: a toilet room, with a wooden cabinet that special visitors might use (it would then have to be carried out of the house and emptied—a very labor-intensive way of marking the importance of special guests).

We have one more night in Thimphu and set off the next morning. Once again, tiny Bhutanese women are carrying our heavy bags and fending off our attempts to take care of them ourselves. “It is our duty!” they tell us. “We have to train our children!” we reply. They win. Jigme gives James his phone number and tells him to call in six days: Jigme has loaned his phone to a friend in need and won’t have it back for another six days. He and his wife live in Trashigang and may be east sometime in August. We will hope to reconnect with them there.