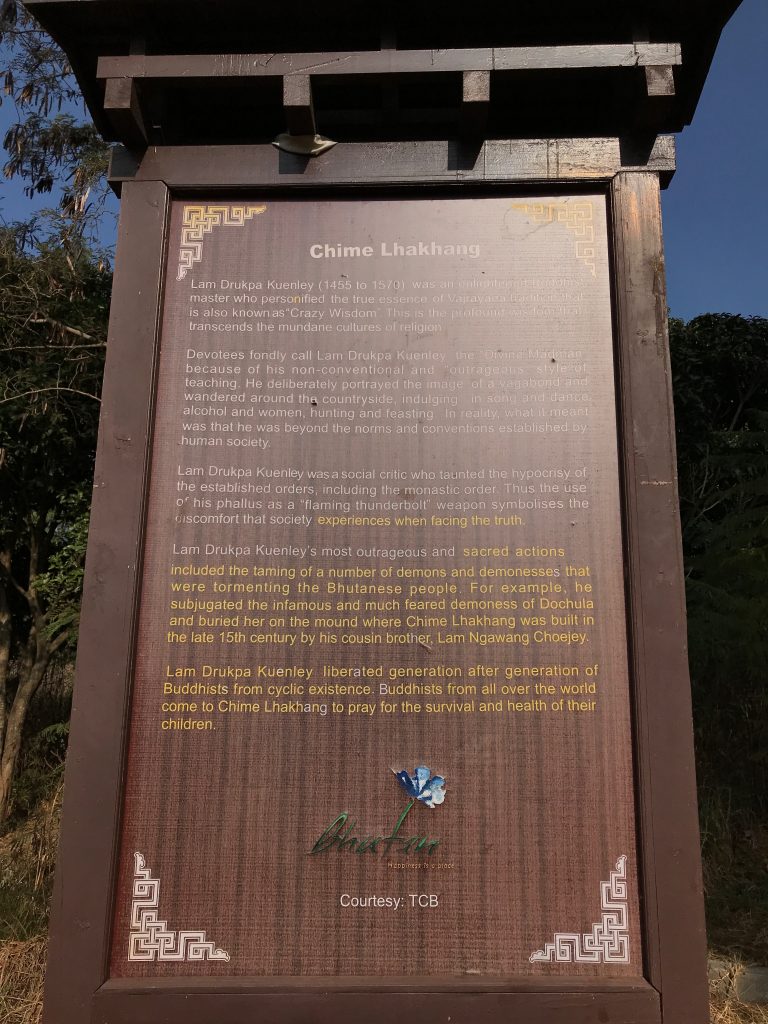

Ugyen was very concerned about our plan to visit Chimi Lakhang, founded by the “divine madman” Drukpa Kinley. “We don’t normally go there with our families,” he said. Not to worry, James told him: Jeremy had already had an eye-full of yab-yum statues. “There are many statues,” said Ugyen, somewhat repressively. But in the end, the lakhang was very restrained. True, we did receive a blessing from two phalluses, one of wood and the other of bone, tied together with ribbon, followed by a blessing from Drukpa Kinley’s iron archery set.

But the prayer wheels around the outside of the lakhang had elegant slate carvings behind them; the courtyard with large Bodhi tree was very peaceful; and the monks were deeply engaged in their rituals.

Granted, the shops below the lakhang were full of phalluses, but I think those were aimed at tourists for the most part.

Then we drove north, to the Khamsum Yulley Namgyal Chorten. We parked where a raft trip was getting ready to launch, and then started the trail by crossing the suspension footbridge.

Punakha is so warm that people can grow two crops of rice each year. As we walked through the fields, we saw people plowing and sowing seeds for the new crop, using a variety of methods.

The chorten itself was stately and elegant.

The inside (no photos allowed) was remarkable in its display of figures. Here’s what I want to figure out: on several levels the focus seemed to be on five statues, in five different colors, all representing what seemed to be a single wrathful figure (in yab-yum). There seemed to be a squashed human figure behind the coupled deities, and a squashed elephant as well. Who were they? Why were they featured here?

Circumambulating each level, we climbed three stairways, prostrating at every level, and pondering the meaning of the statues, until we reached the roof. The views up and down the valley from the roof were expansive and heart-expanding—which was helpful, since we were a little weighed down by family squabbles.

Coming down from the chorten was an easy saunter; we snacked beside the river on oranges and bananas (butter bananas, Ugyen says this particular version is called), watching another set of rafts launch. Then we piled back in the car and drove to the Punakha dzong.

Punakha dzong

We had to pay full tourist fees to enter the dzong (instead of the 10% we pay as residents elsewhere)—but a guide was included in the price. Poor Wangdi, who was assigned to us, didn’t really know what he was getting into, but he was patient and thorough in his attempts to answer my many questions.

The main and largest courtyard is for administration of the dzongkhag; it’s also the site of the annual dances during the five-day tsechu.

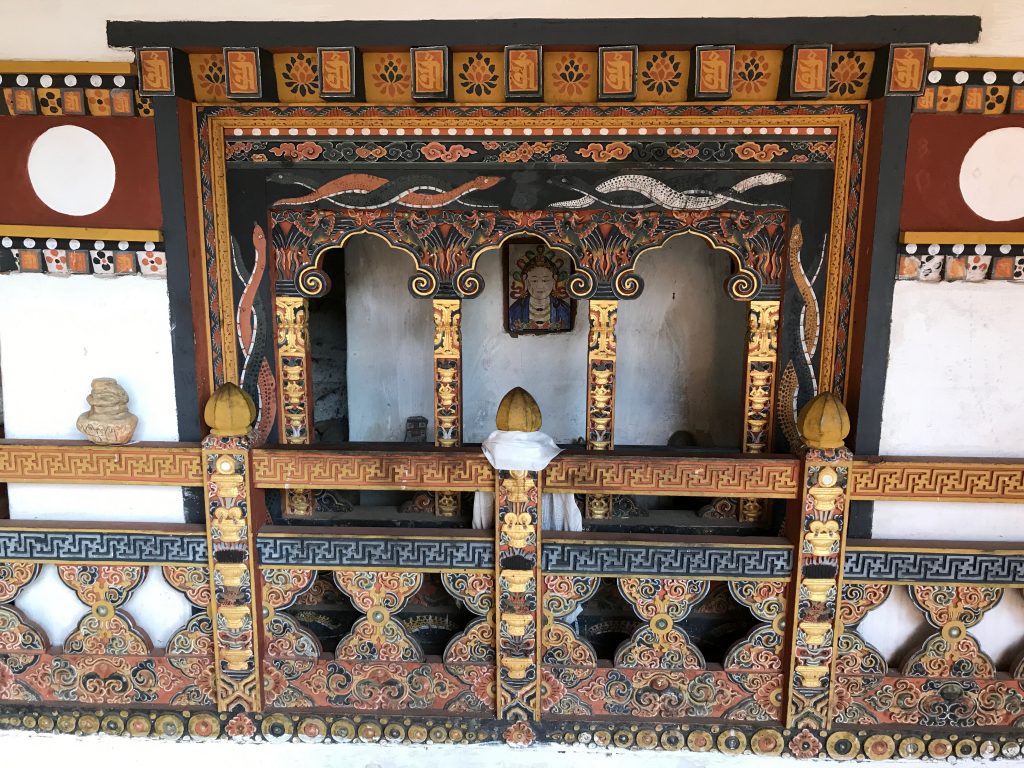

We were interested to hear that the shrine to the queen of the nagas was created to mark the fact that the Zhabdrung, when he first arrived in Punakha, granted this place to the ruler of the nagas. In gratitude for this gift, the ruler of the nagas offered up the stones used to build the dzong (and there was a pile of leftover stones behind a glass wall in token of the gift).

The second courtyard is ringed with rooms occupied by monks. The two courtyards are separated by the utse, or a building containing a series of temples dedicated to the use of the monks. Wangdi said that the monks use this second courtyard as a green room, before passing through the narrow corridor into the first courtyard when performing their dances.

The third courtyard opened onto three temples: one, full of eight stupas, used to be open to tourists, but has been closed because of the hassle tourists cause; another is open only to Bhutanese subjects on the first two floors, and the third floor, containing the Zhabdrung’s body, is open only to the kings, the Je Khenpo (chief abbot), and a guardian monk who makes offerings in front of the Zhabdrung’s body. (The Zhabdrung entered the room when he was dying and he began his final meditation there—I’m not sure whether he’s supposed to be still meditating, or whether his body is understood to be preserved even after his spirit has left. If you’re a spiritual master, I guess you get to manage endings however you like.)

We heard some stories of the Buddha’s life we hadn’t heard before. Evidently, the story of his life is traditionally told in 12 panels or paintings. (No images since we were inside the temple, but the narrative may be of interest to someone, if only myself when I’ve forgotten the details of our trip.)

1. Buddha preaching to the gods in Tushita before his birth. Tushita is the heaven where Siddhartha lived as a fully realized Buddha before coming to earth; it’s also the place where bodhisattvas live before they come to earth to achieve full enlightenment.

2. Buddha’s mother, Mahadevi, dreamt that a white elephant came down from heaven to enter her womb from the right side. Mahadevi in Sanskrit and Hinduism is known as the “great Goddess.”

3. Birth: Buddha was born from his mother’s rib (!) and takes his first seven steps, with a lotus blooming from each step.

4. Accomplishments in worldly arts. Evidently, the young prince demonstrated superhuman powers: the ability to lift and throw an elephant (!), the ability to fly or float above water that would wash other men away, talent at archery, and more.

5. Marriage and four excursions. He was married to his cousin at age 16 and gave birth to a son, after which he ventured outside the grounds of the palace and discovered suffering (of birth, illness, age, and death), leading him to renounce his princely life and his family.

6. Renunciation. His charioteer or driver, who took him on the four excursions, wanted to come, but was sent back.

7. Life as an ascetic. Images here are of the skeletal or starving Buddha. He practiced severe asceticism from the age of 29 to the age of 35 and gathered five followers. One day he collapsed after nearly starving himself to death. A village girl named Sujata fed him some milk or porridge, saving his life. Then he began following and preaching the “Middle Path.” His five followers turned against him.

8. Meditation under the Bodhi tree. He meditates for 45 days…

9. Conquest of Evils (Mara). Mara, personifying all forces that block enlightenment, tries to seduce and distract Buddha during this period of meditation. Mara sends his beautiful daughters to seduce Buddha and then they and other demons shoot arrows, spears, fire, etc. at the Buddha. Instead of being distracted, Buddha realizes the four noble truths. Mara’s daughters appeared as beautiful female figures to distract him, but he turned them into ugly forms; after his enlightenment, they asked his forgiveness and asked to be made beautiful again. He granted that wish and they became protectors of the faith.

10. Buddha’s first teaching was given to the Hindu gods Indra and Brahma, who changed themselves into deer for the teaching. The Buddha didn’t want to give his first teaching to a select group of humans, for fear this would create jealousy through injustice, so he gave his first teaching to the deer in order to inspire all humans. Then he gave his second teaching to the bikkus (the five earlier followers who turned against him and then became arhats, or holy men and his first disciples).

11. His mother, who had passed away before his enlightenment, had seen his suffering as he meditated below the Bodhi tree, and she let fall a tear drop. Thus, after his enlightenment, he returned to the heavens in order to share his teachings with her and others. He spent quite a long time there and the Hindu gods had to plead with him to re-descend to teach humans, this creating the descending day of Buddha (a national holiday in Bhutan).

12. At the age of 80 (8), Buddha was fated to die, but being Buddha (and thus having achieved enlightenment), he extended his life for 3 months and then, in order to model impermanence to all living things, he chose to die. His image here is known as “reclining Buddha” but some call it the dying Buddha.

I might have left out or muddled part of this history, but this is what I took away from the discussion. There’s a slightly different version of this 12 panel story (with some images) at http://www.beprimitive.com/blog/buddha-room-paintings-the-12-stages-of-buddha-s-life

Wangdi also told us that the three hanging fabric pieces in temples (fain, gyeltshen, and chebor gyeltshen) stood for the Buddha’s earring, his body, and his clothing. Who knew?

Jeremy, meanwhile, was delighted to get confirmation that Vajrapani is indeed the same as Chana Dorji (vajra = dorji, after all)—though he was disappointed that Wangdi could not find an image of Milarepa among the many followers of Buddha portrayed on the walls. Jeremy also received a more authoritative answer to his recurring question of whether or not the Buddha achieved enlightenment in his first lifetime (no: he was reborn many times as an animal and in other forms, hence the Jataka tales).