On Saturday, March 8, we set off on the first of three Ecocriticism study tours, to an agricultural research station, or a Research and Development Center (RDC) for Renewable Natural Resources (RNR). For me, the field trip was a masterclass in how you can’t know what you don’t know.

I didn’t know how far we had to go. After the trip was booked and confirmed (for a single day), the dean said to me, “I thought you would take two days for the trip.” Oh well. I thought the drive was 2-2.5 hours each way, but it took us 4 hours each way on the bus.

I didn’t know, until after we missed the open hours for the roadblock, that there were established hours (and the road closed at 8 am, not–as my vague impression had it–at 9 am).

Above all, I didn’t understand the local culture around field trips. “Should everyone go? Why not just the group working on climate adaptation? What do you mean, the others will just wander around while the focus group interviews the experts?”

Live and learn.

The students started off some 20 minutes late from Yonphula. Then they stopped in Kanglung, not just to pick up faculty members but also to buy water and doma (betelnut) for the trip. If I had known that this would put us an hour and forty minutes behind…. Maybe it’s just as well I didn’t know.

The first part of the road from Trashigang to Mongar is rough, but very beautiful.

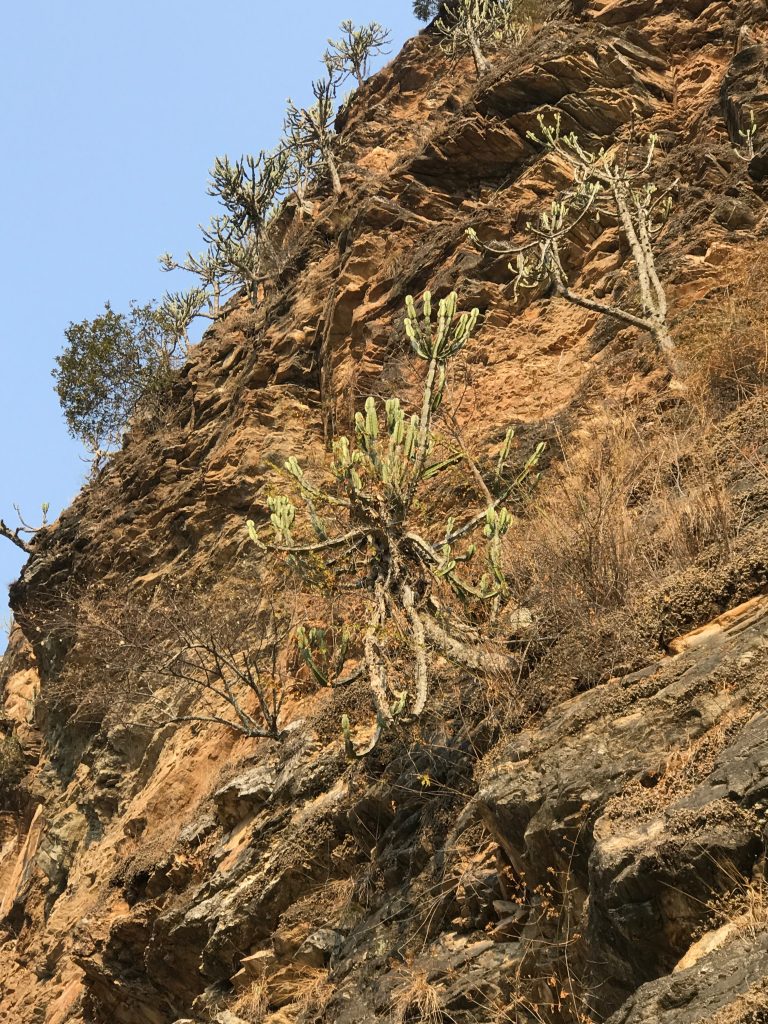

The roadblock is well set-up, with a small hut offering snacks–tea and momos. Because I’m a plant geek, I was struck by the cactus helping hold the hillside in place.

My students decided to walk through the construction site and wait for the bus on the far side. This involved one of the students going up and tapping on the window of each of the first two diggers, asking them to let us pass. With the third digger, we just ran through its arc as it swung to the cliffside for another load of rocks and rubble. Not like any field trip I could imagine in the US.

My students are good foragers. Here, Rakesh has found curry leaves, and Pema Gyelpo and others are knocking tamarind pods off the tamarind tree.

The soap-making factory the students had wanted to visit was closed, but while we were waiting at this bridge for the bus to rejoin us, the Dasho (a title of high honor) from Wengkhar called to find out where we were. Hearing that we had only reached the roadblock, he abandoned the plans to give us two presentations on climate change adaptation, and left one field officer in place to give us a tour of the station. Aargh! I was embarrassed and frustrated, but the students were unbothered. “They could have waited for us,” was the general response. But we were hours late! Bhutan stretch time rules…

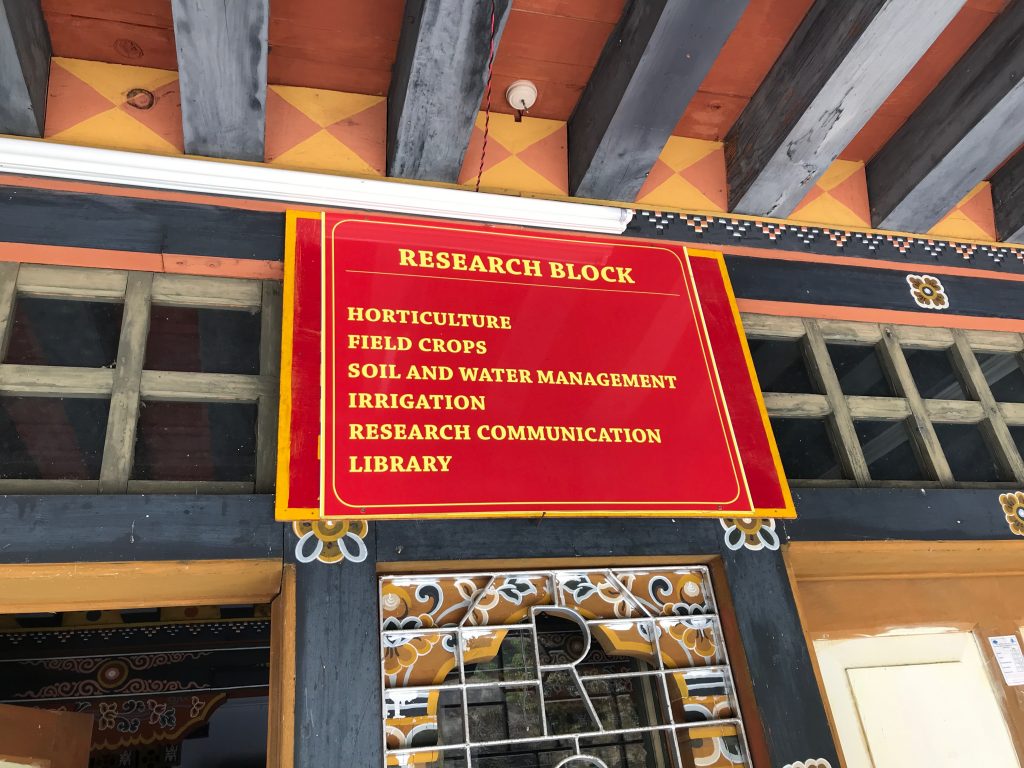

The main buildings at Wengkhar are beautiful and well-kept. The plantings attest to the station’s attention to plant growth.

The emptiness attests to our late arrival.

Our poor tour guide pointed out that if he didn’t live at the station, he too would have left to pursue personal affairs. But we were so grateful for our tour of the grounds. I liked acquiring the name of the Chinaberry tree (so pretty, but useless, as my students point out):

I also learned that the fencing tree is a kind of a fig! When I said that our figs in the US produce fruit that we eat, Shacha said that the same was true in Bhutan, and that the figs were fed to pigs also–which makes me think we’re talking about very different fruits.

The permaculture block is a work in progress, with a visit planned to a permaculture center in Nepal. Wengkhar staff want to learn about permaculture, while the Nepali center wants to learn about Wengkhar’s lead farmer program. (Lead farmers come to Wengkhar for extensive training and resources and then they become training centers, passing on dividends to other farmers in their vicinity.)

The main crops explored at Wengkhar include hardy kiwi and citrus

including more exotic kinds of citrus like loquat. Tangy! (Their kumquats were incredibly sweet, however.)

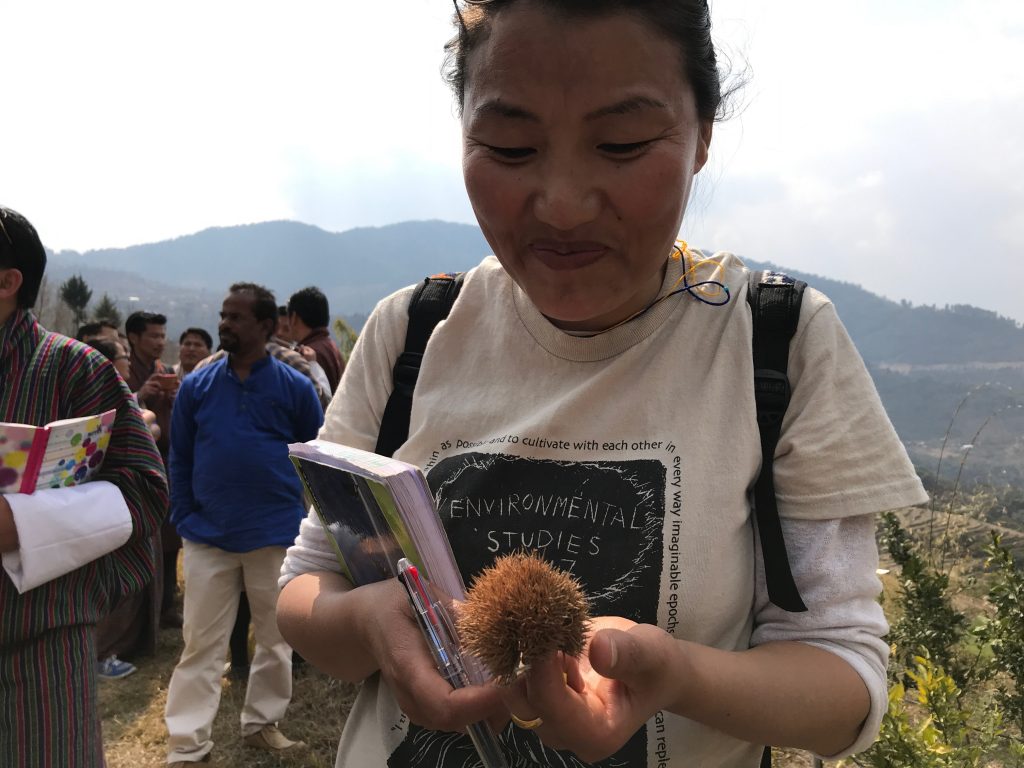

Phubee found the chestnut shells bizarre in their spikiness.

For the younger generation, the Wengkhar staff emphasize modern features such as hoop-houses and automatic watering systems–strategies that seem less like subsistence-level farming to youth who are tempted to migrate to the city.

It was all quite fascinating! But, as I discovered at the end of the tour, the real purpose of a study tour is the picnic lunch! That was why people were late leaving Yonphula–because they had been up since 4 am cooking lunch!

In the end, a fine time was had by all. It was certainly a field trip like no other I have ever been on!