After we got back to Rangjung from Merak, we transferred to an open-bed truck to make the rougher trip to the trail head to Sakteng.

It was all good fun–except when the dust and fumes were particularly strong.

The road wound past small towns–hillsides full of smallholdings–and around streams guarded by water-turned prayer wheels.

Once we got to the end of the road, there were ponies waiting to carry some of the food the students had packed (heavy potatoes). The truck driver planned to spend the two nights until our return. We started off on a path marked by landslides from the blasting for a new road–and before long, we found ourselves hiking over charges of dynamite set for further blasting. The valley will seem very different when seen from a motorized vehicle on a paved road, we all felt.

Sonam Norbu stopped to chat with some friends who were working on the road.

I looked down and saw the fuse wire set to blow some more explosives for road clearing. The men warned us there would be more blasting ahead.

The path wound through red and white rhododendrons, and we passed cattle returning for more loads from the trailhead.

Chador offered me some dough designed to ward off altitude sickness. “What’s in it?” I asked. “Flour, oil, arra…” the students started listing all the ingredients. “But what makes it good against altitude?” “The arra, of course!” they said, and everyone laughed.

There were many rest stops along the way, the final one just over the crest of the hill above Sakteng, where the land has been grazed down and the hills open up. These Brokpa men were amused by us–you can see the difference between the serious look donned for photos and the broad amusement that tends to happen off-camera.

This ancient ceremonial arch marks the final (lower) hill before the main village. The hills before that arch are covered with grazing yaks.

The village itself feels more open and spacious feeling than Merak did.

Here, men spin and women weave. These people are working in the courtyard in front of the store across from the school.

Inside the main wall of the school, we foreigners are given the principal’s empty house as temporary quarters: we all gather around the bokhari for tea and biscuits.

The next morning, we watch as the children sing at the raising of the flag, then run for their bowls, wash their hands, and gather again to sing for their breakfasts.

After a spell of trying on Brokpa clothing, we start climbing up to the two lhakhangs above Sakteng.

I admired the portraits of the four geps. The students hung prayer flags,

and we took a group photo with the temple caretaker.

It was a beautiful temple.

We went galumphing down the hill to head over to the second lhakhang.

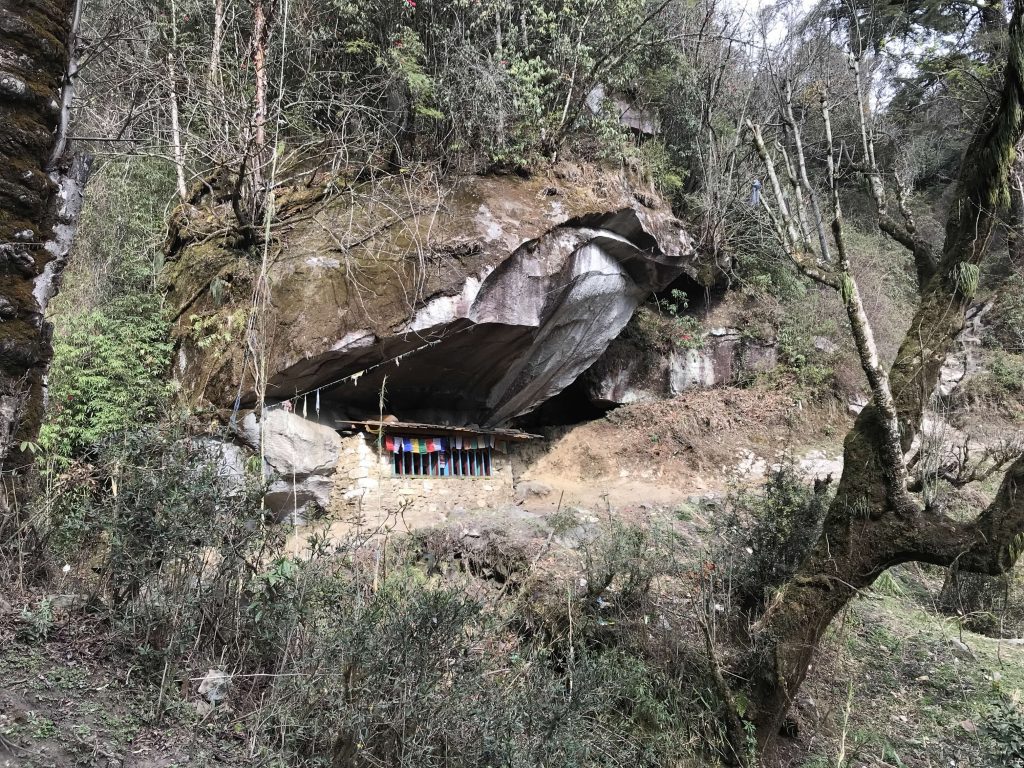

Just below this second lakhang we passed through a major construction site organized for a new goemba (I think). We were supposed to test our karma by trying to match the footprints of an enlightened lama–even with a running start, my steps fell short (of course!)

The caretaker of the second lakhang shared a selfie with me: it’s unusual for women to be caretakers, and so it seemed especially unusual for both lakhangs to have female caretakers–perhaps, the students said, as a result of Aum Jomo’s power in these parts.

From the perspective of this lakhang, the first seems distinctly lower. But the story of the two lakhangs goes something like this: a student of the master of the first lakhang builds the second lakhang for himself and then is mortified to find that he has placed himself above his master. He offers to trade lakhangs with that master, but the master refuses, saying that the student is the reincarnation of the master’s own master, and so it is just and correct for the student’s lakhange to be higher. The friendly dispute is resolved by GPS, which proclaims that the two lakhangs are exactly level, despite appearances to the contrary.

Sakteng means “the place of bamboo”and the uses of bamboo are extensive.

I found this low fence particularly elegant in its design and execution.

After our trip to the lakhangs, we had chosen to stay inside during the afternoon rain and hail storms rather than going to “Aum Jomo’s place,” so the next morning, before we left Sakteng, our hosts led us over to this final lakhang, passing through a sheep yard on the way. We would pass by Aum Jomo’s cattle, they told us–not these sheep, but rather a set of mossy stones.

An effigy of Aum Jomo

At the last lhakhang we visited in Sakteng, one of the masks from the tercham dance makes an intriguing pair with the portrait of the king

Outside, the stream that runs below the lakhang down to the river is shown to us as evidence of a pillar within the temple that periodically oozed water.

We paused for a group photo at the stone arch, and then paused again to look at the path down to the bridge, the water-turned prayer wheel, past the beautiful yaks and the close-cropped grass.

Then we traveled down the path, past the now-visible warning about construction (“beware dynamite” could still be more clearly stated), various men carrying building materials up the narrow path, children not in school, a walnut seller from Phongmey.

While the mountainside shows the effects of blasting, most cargo is still transported to Sakteng by human or pony labor. We passed these folks near the place the path connects to the existing road. The bags of noodles puff up because of the air pressure at altitude.

Jeremy led the teachers in a game of “BS!” on our rainy ride out.

For me, this photo of a major digger dwarfed by a landslide epitomizes some of the complexity of road building in Bhutan.