Waking up at the Swiss Guest House was a beautiful thing, even before breakfast.

Jampey lakhang

Our first day in Bumthang, we visited a couple of monasteries. First, the tiny and ancient Jampey lakhang: the oldest temple in Bhutan, built by the Tibetan king Songtsen Gampo in 659, on the same day as Kyichu Lakhang in Paro. The goal was to subdue a demoness: Jampa lakhang pins her left knee; Kyichu Lakhang pins her left foot.

In the parking lot, we saw the stupa or pile of mani stones, in a form said to be dedicated to the guardians of the four directions—also known as the four kings. In each corner of the large courtyard there is a stupa of a different color—white, yellow, red, and blue—also helping to anchor the lakhang. In the back of the temple, there are two square stupas, and you’re supposed to go around the outside of those stupas, ignoring the prayer wheels in the temple walls, luring in the unwary. We circumambulated the temple, spinning the prayer wheels, each with handles deeply worn by decades of worshippers. Then we walked through the entry, flanked by two large prayer wheels on each side, into another, smaller courtyard, with the Jampa lakhang directly ahead. Each time we visited, an elderly woman was doing prostrations in the courtyard.

Crossing the courtyard and removing our shoes, we could hear a monk chanting. At the door of the temple, we bowed to him, sitting next to the throne, and we crossed the temple to the doorway of the space where Jampa or Maitreya, the Buddha of the future age, could be seen. The guidebook says that the stone steps here represent the past, present, and future. The past (the age of Sakyamuni Buddha) has already sunk into the ground and is covered by a wooden plank; the present step is a few inches above the floor, and when it sinks to ground level, supposedly gods will become like humans and the world as we know it will end. Then the future age—the third step, and the time of Jampa—will come into being. Guru Rinpoche is supposed to have meditated in the alcove above the entry, leaving a footprint behind; he is also supposed to have hidden treasures in a lake buried under the temple.

On the south of the temple, there is another temple with statues of Guru Rinpoche, Tsepame, and Chenrezig. The passageway between the two temples includes ancient armor hanging on the walls.

Outside the temple, two women were selling various wares. We bought a set of yak-bone prayer beads for Jeremy and me to share, along with a hand-woven scarf.

James and I came back to Jampa lakhang on the afternoon of our second day in Bumthang because we hadn’t managed to see the promised demons of the bardo. We timed our visit badly—4 pm services were happening—and so while we did manage to visit the Jampa lakhang again and we found the kora path, a corridor around the central lakhang, lined with images of 1000 buddhas, we didn’t bother asking anyone to open the Kalachakra lakhang in the northern side of the courtyard. I guess I’ll just have to meet the demons of the bardo without any prior introduction….

The Jampa lakhang seems to be most famous for the naked treasure dance included in its annual tsechu, but we were glad to be here at a quieter time.

Kurjey lakhang

After the Jampa lakhang, the sheer size of the Kurjey lakhang was a bit of a shock. The courtyard itself is imposing, enclosed by a wall with 108 chortens, and the facades of the three temples are glorious. We liked watching and listening to the birds wheel around and return to the rafters time after time.

We went into the third temple first—a temple built by Ashi Kesang Wangchuk, queen to the third king, under the guidance of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. On the wall outside the temple proper there was a “mystic spiral” mandala on the left hand side and a wheel of life on the right hand side. The most impressive part of the temple, though, was the wax figure of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche inside the temple, with a hand raised, looking so lifelike that several of us actually thought he was alive for a few minutes.

The second temple, built by Ugyen Wangchuk when he was penlop (a regional ruler, before he became king) contains a huge statue of Guru Rinpoche along with his eight manifestations.

The entrance to the first, earliest temple, the Sangay lakhang, is on a lower floor (up a flight of stairs, so it feels like a second floor). There was a boarded-up passageway (boarded up to keep out wild dogs) you can crawl through to leave your bad karma behind. Jeremy and I crawled through—it was a little dusty, but not too tight a squeeze. Then we all went up another flight of stairs to the lakhang proper, where statues of Guru Rinpoche and his manifestations rest in front of the (tiny) opening to the meditation cave which holds his body print (kur: body; jey: print).

Guru Rinpoche first came to Bhutan in 746, when he was invited to Bumthang to intervene in a local power struggle. Two Indian kings had established strongholds in Bhutan: one, known as Sindhu Raja, established himself as king of Bumthang, while another, known as Naochhe (big nose) held power in southern Bhutan, where he killed Sindhu Raja’s son and 16 attendants. Sindhu Raja, in a fit of rage, desecrated “the abode” of the local deity, Shelging Kharpo, who turned the skies black and took Sindhu Raja’s life force, leaving him near death. One of Sindhu Raja’s secretaries invited Guru Rinpoche, already known for bringing Buddhism to Tibet through various magical feats, to come to Bumthang to save the king.

Guru Rinpoche meditated in the cave at Kurjey, leaving behind his body print. Then, as part of the process of recovering Sindhu Raja’s life force, Guru Rinpoche was supposed to be married to the king’s daughter. He sent her away to fetch some water in a golden ewer or pitcher, and in the meantime, he transformed into all eight of his manifestations and together they began to dance in a field by the cave where he had meditated (perhaps now the temple courtyard). Every local deity except Shelging Kharpo came to watch the dance—but Shelging Kharpo was the point of the exercise. So when the princess came back, Guru Rinpoche turned her into five separate princesses, all with golden pitchers. The light flashing off the pitchers finally caught Shelging Kharpo’s attention, and he turned into a white snow lion to come and see what was happening. Guru Rinpoche turned into a garuda (a mythical bird) and swooped down to battle with the snow lion. Caught by surprise, Shelging Kharpo gave up Sindhu Raja’s life force and agreed to be one of the protector deities of Buddhism. To seal the deal, Guru Rinpoche planted his staff in the ground at the temple and it flourished as a cypress tree. He then converted both of the warring kings to Buddhism, bringing peace to the kingdom.

Do Zom, the suspension bridge, and Tamshing goemba

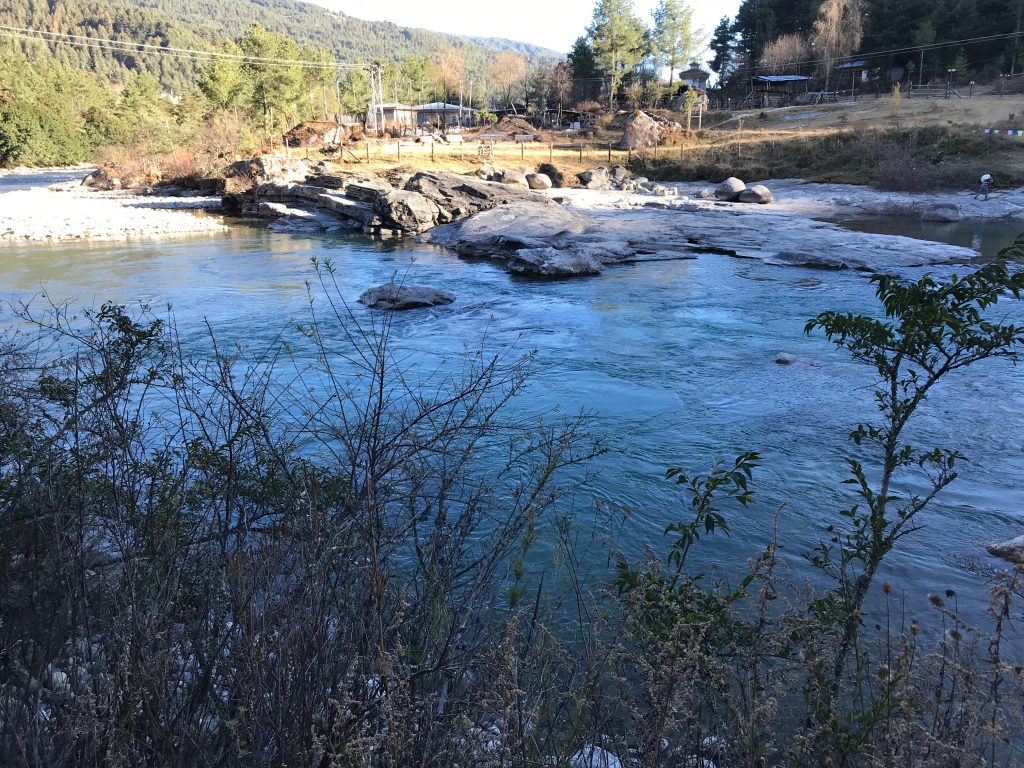

After a late lunch, Ugyen drove James, Jeremy and me over to Tamshing goemba, apparently established in 1501 by Pema Lingpa. Lonely Planet says it’s the most important Nyingma monastery in the kingdom, but it doesn’t say why. We arrived around 3 p.m., just as hordes of Bhutanese folk were arriving. We thought we wouldn’t interrupt whatever was happening, so we left Ugyen with the truck while we walked up to a suspension footbridge by the Do Zom, which is said to be the remains of a stone bridge built by a goddess who wanted to meet Guru Rinpoche.

The bridge was destroyed by a demon, according to the story. Jeremy loved the footbridge, and James found it all very meditative.

Back at Tamshing goemba, an overtired Jeremy rested in the car while James and I went in. We loved the courtyard of the first entryway. (No photos, because I left the phone with Jeremy.) Circumambulating the temple, we passed a bird-feeding table, full of ravens coming in to feed for the night. Inside the lakhang, we followed the walls covered with paintings attributed to Pema Lingpa himself: they have the same feeling as old unrestored frescoes in Renaissance Italian churches. In the inner building of the temple (a building inside a building) the monks were chanting, carrying offerings, blowing horns, banging drums with a rhythm like that of a heartbeat (heavy beat, light afterbeat). We sat in a corner for a while and then went to rejoin Jeremy and Ugyen.