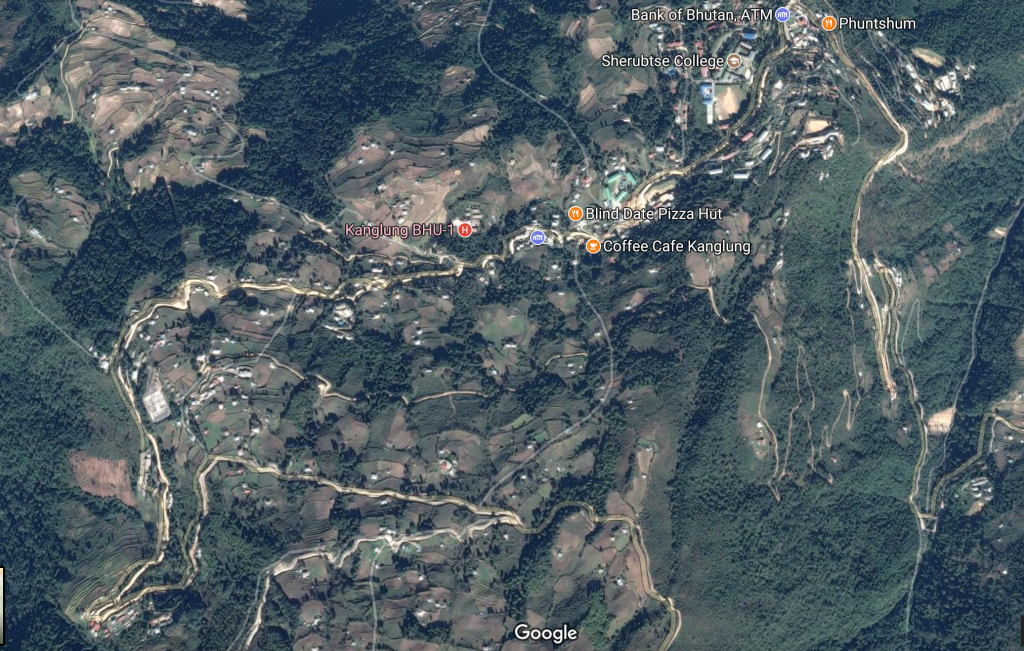

James comes with me to meet the president. We wait with Thinley for a while in the hallway outside the office as others come and go. When the president is free, we are ushered into the office. He sits on one side, with a small table before him; the three of us sit on the far side of the room—a great distance, by American standards. (This is a Bhutanese norm, I think, since the same seating arrangement held for my conversation with Thinley and Chitra (Thinley against one wall, Chitra and I against the far wall).

By contrast, the president is warm, frank, and engaging—as charismatic in person as he seemed in his emails. He mentions the road, and says he suggested going the India route, but our visas did not permit. (This is a stronger statement than we heard from Ugyen at the time, perhaps in part because Ugyen was nervous about that India road—or perhaps because of our single-entry visas.) He apologizes about the dogs. “Even when we know that it may be harmful to our health, we can’t resist. My younger son, he has been bitten three times, but he won’t stop feeding the dogs and trying to make pets of them.”

He also mentions earthquakes: the epicenter of the 209 earthquake was just a few kilometres away from here (in Mongar district). “Some of our buildings are actually quite scary,” the president confided. “An American was here and he pointed out one building in particular he thought was dangerous: we took it down, actually, and rebuilt it. The older buildings withstood the quake well, but the more recent buildings are not well constructed. We are at the mercy of our construction companies.” Note to self: dig out the components of the planned “earthquake go bag” and make sure that we are in fact ready to go in case of an earthquake. It would be such a pity to have brought the gear and failed to make it accessible.

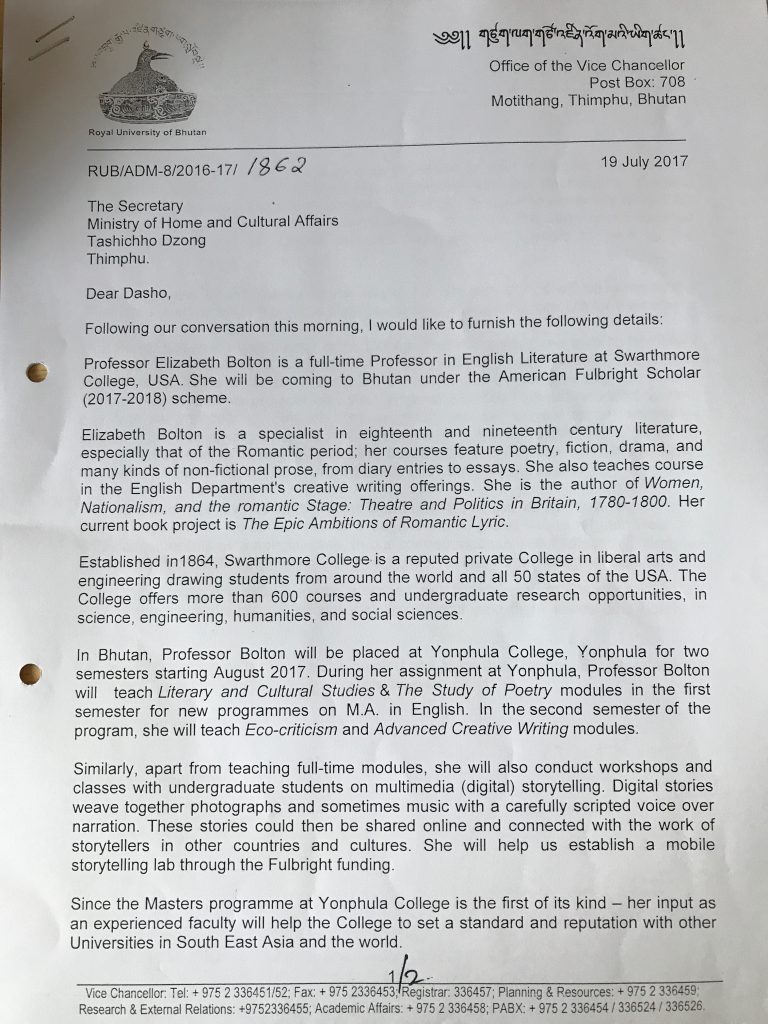

I ask about entrepreneurship—thinking of connections back to Swarthmore’s Lang Center Design Lab—and the president notes that Bhutan’s upcoming five-year plan emphasizes entrepreneurship as a development path for the country.

We also talk about the possibility of Zoë assisting in the primary school and/or taking classes at Sherubtse. At midday, over lunch, the president calls to say that according to his wife the school has already talked about this and chosen teachers whom Zoë will assist. They just haven’t gotten back to us about this conversation.

And the new academic building.

And the new academic building.

Kuri Zampa is the village marking the bottom of the valley—a descent of 3200 feet from the pass. The air is thick and moist here—as it is even in Mongar, though Mongar is significantly higher up the side of the mountains.

Kuri Zampa is the village marking the bottom of the valley—a descent of 3200 feet from the pass. The air is thick and moist here—as it is even in Mongar, though Mongar is significantly higher up the side of the mountains.

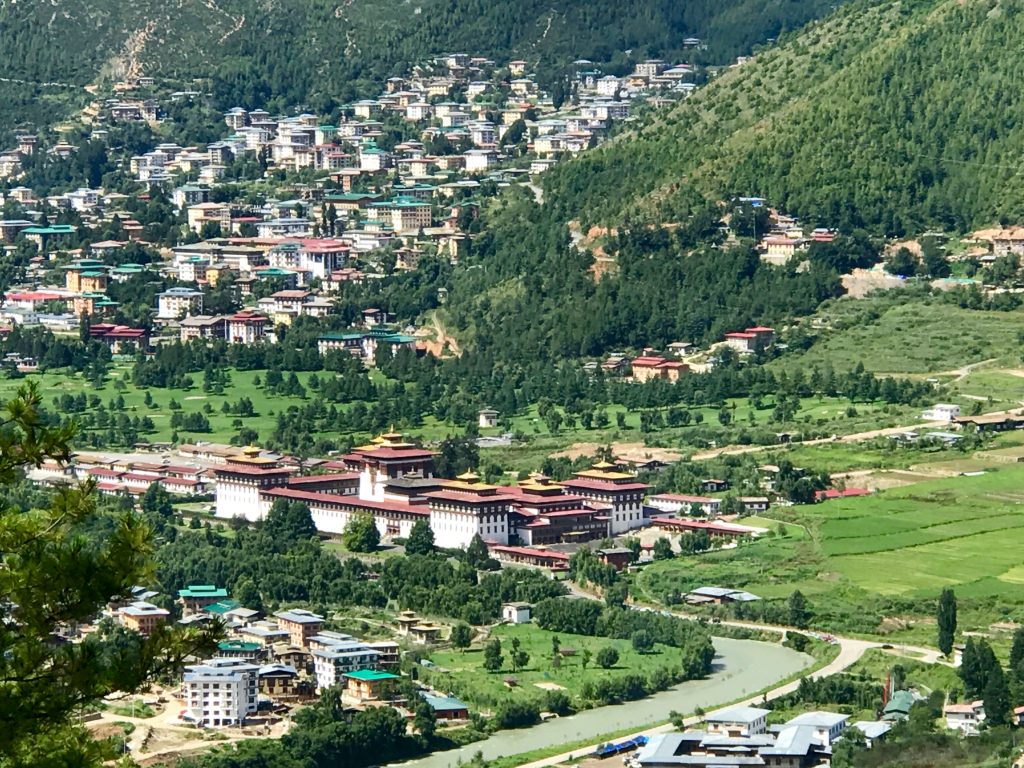

The road to Bumthang winds above the Thimphu dzong and the surrounding rice fields, past Bhutanese on cell phones and Indian workers laboring on infrastructure projects.

The road to Bumthang winds above the Thimphu dzong and the surrounding rice fields, past Bhutanese on cell phones and Indian workers laboring on infrastructure projects.

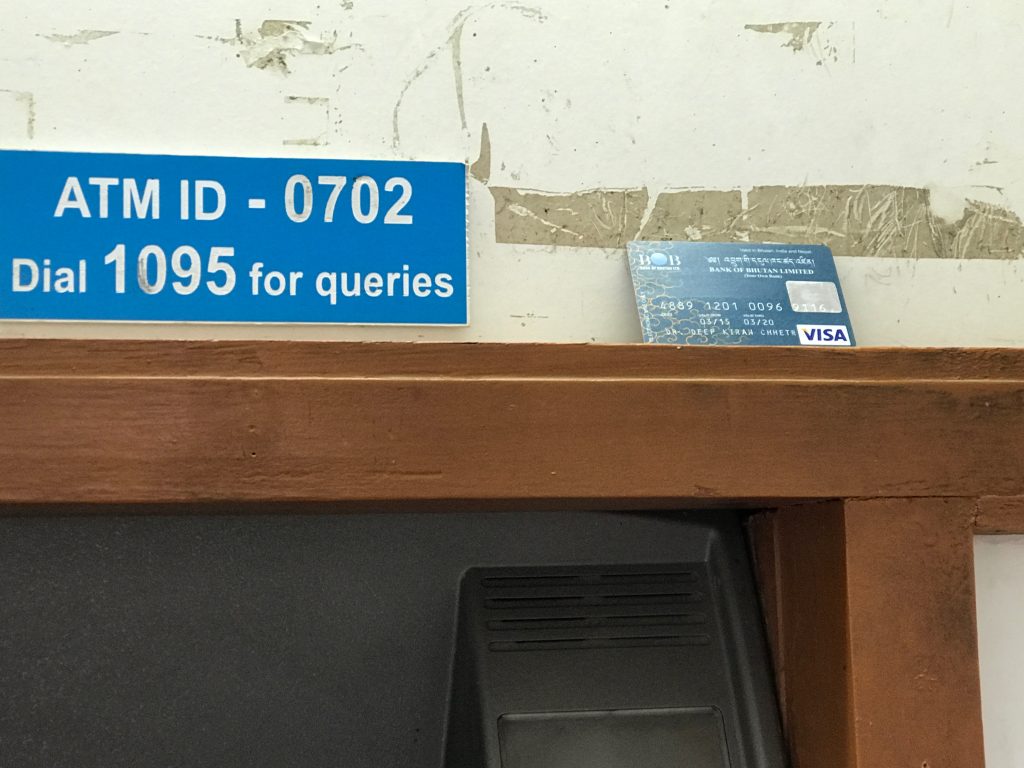

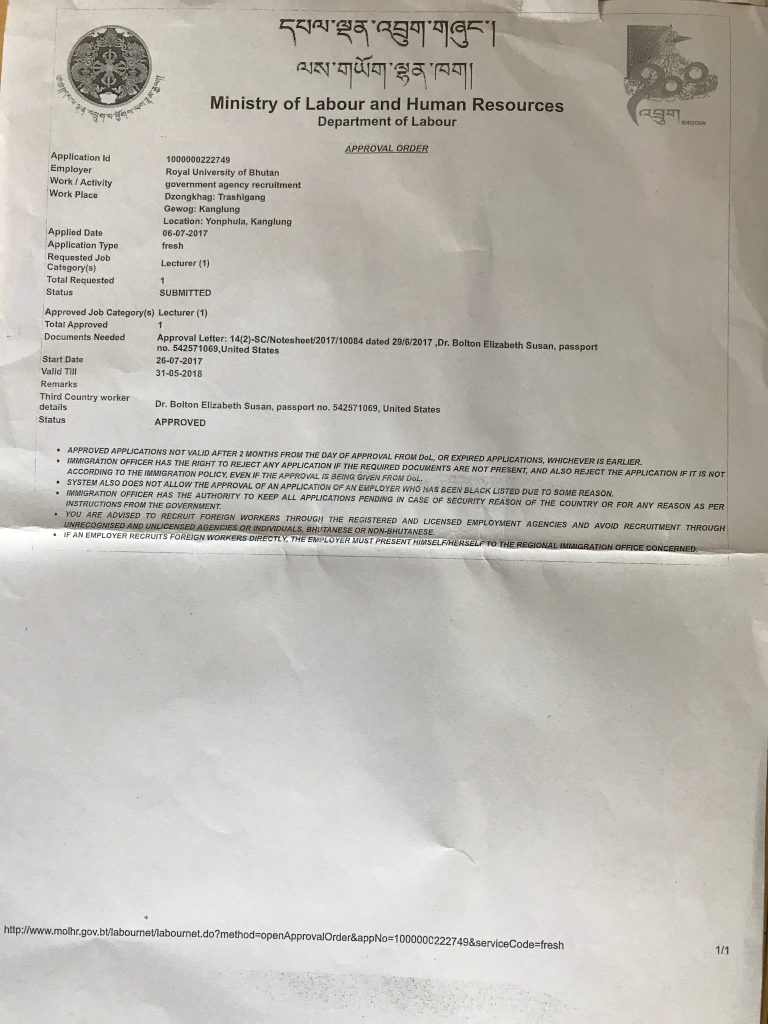

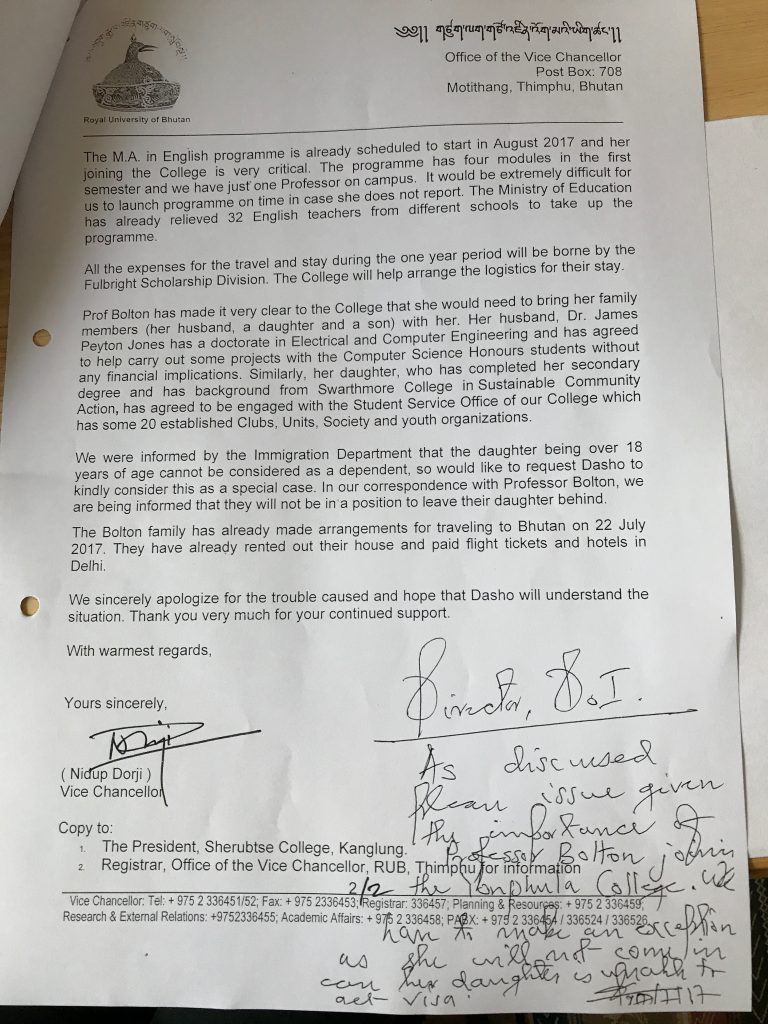

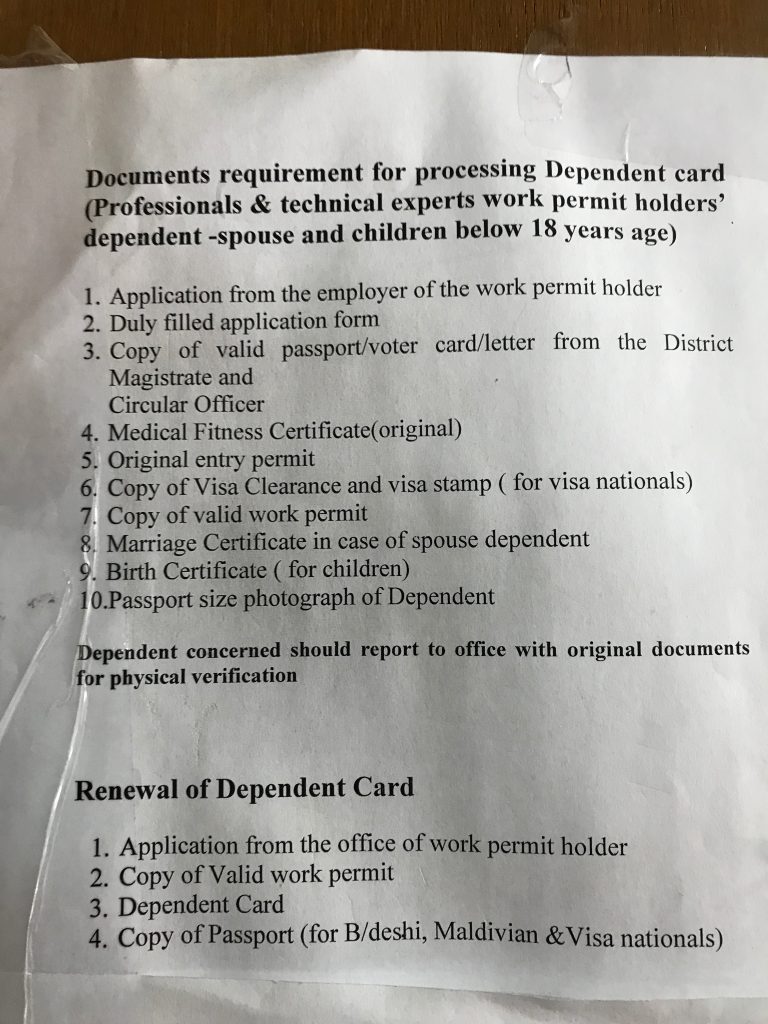

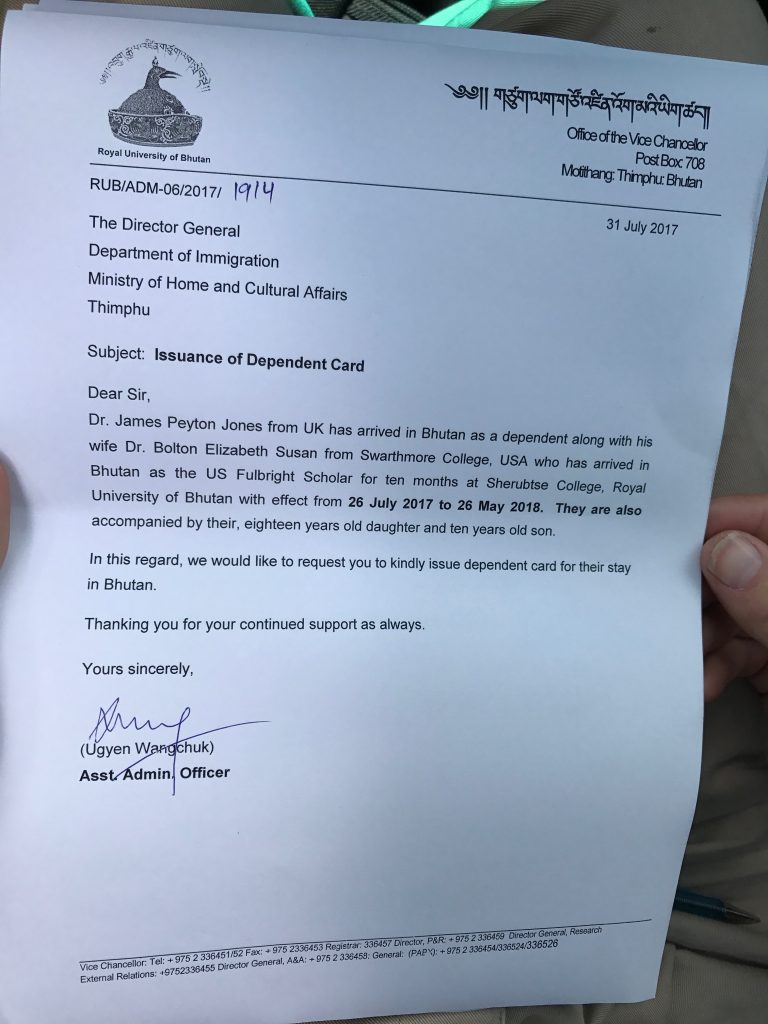

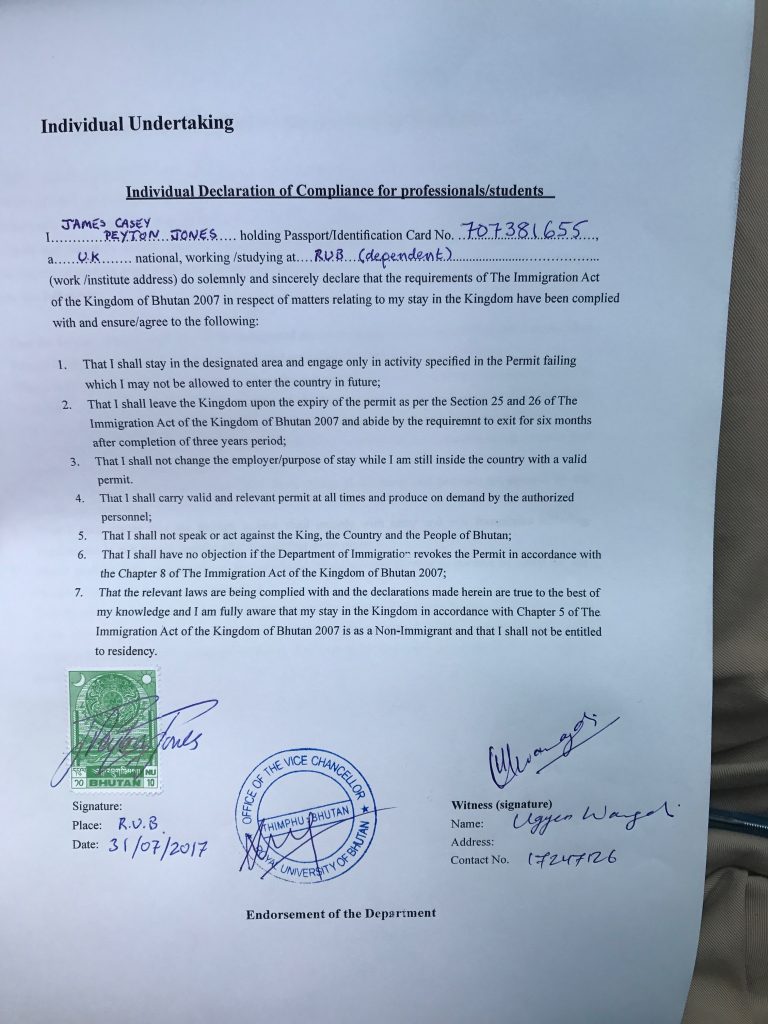

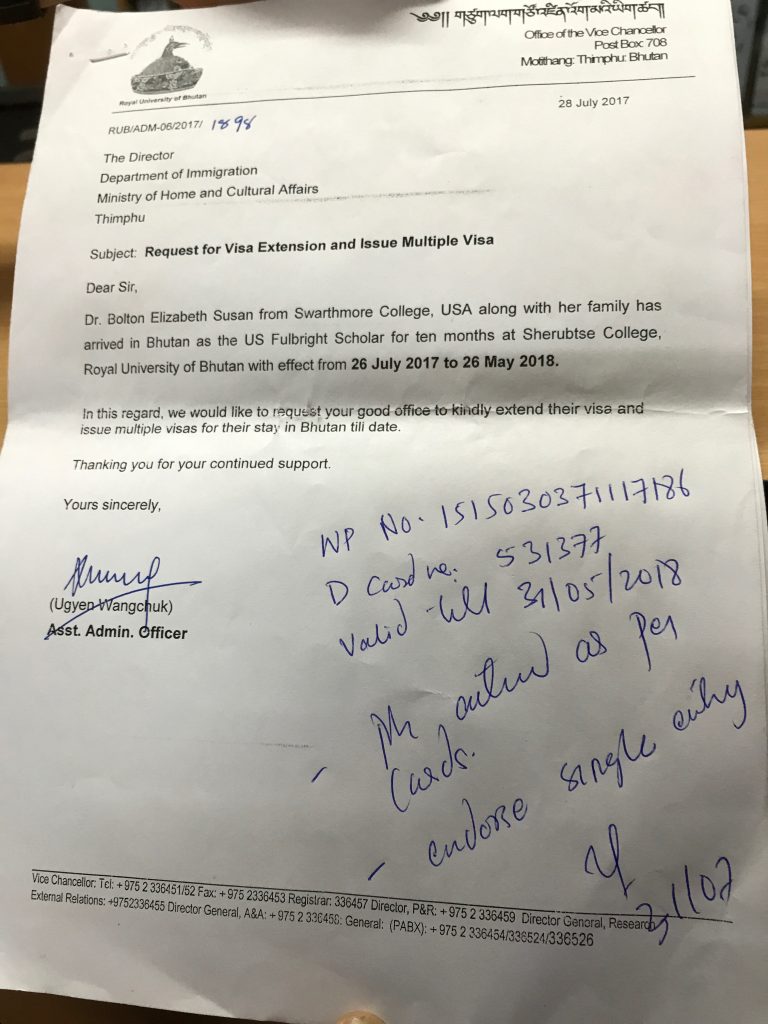

“The visa applications specify multiple entry visas,” the head officer explains. “But that’s quite expensive: 24,000 ngultrum per person.” Given that we can only take out 10,000 ngultrum at a time (and that’s $150, we decide to stick with a single entry permit for the moment. Off we go to a cash machine, then to a different desk to make the payment and get a receipt, then back to the head officer, then out to a different counter for the actual visa stamps.

“The visa applications specify multiple entry visas,” the head officer explains. “But that’s quite expensive: 24,000 ngultrum per person.” Given that we can only take out 10,000 ngultrum at a time (and that’s $150, we decide to stick with a single entry permit for the moment. Off we go to a cash machine, then to a different desk to make the payment and get a receipt, then back to the head officer, then out to a different counter for the actual visa stamps.

On Sunday, Ugyen insisted that we visit the temple Dechenphu Lakhang, to make prayers and offerings for a safe voyage.

On Sunday, Ugyen insisted that we visit the temple Dechenphu Lakhang, to make prayers and offerings for a safe voyage.