In the morning, it was raining, at first lightly, and then in earnest. This did not actually seem like a blessing, because Sonam had proposed to go on a picnic up to Yonphula, and Jeremy was excited at the prospect. We brought in the bucket and took turns splashing the blessed water over us (some more seriously than others) and having a shower. Then, I made oatmeal for me and Jeremy, because we had heard the traditional breakfast for Blessed Rainy Day was porridge. Then, around 8:30, Sonam arrived at our door, bearing actual Bhutanese porridge and cookies. The porridge was rice porridge–rice cooked until it dissolves into a kind of salty soup, seasoned with just a little chili, and with cubes of cheese floating in it.

Not at all what the word “porridge” had brought to mind, but it was good–especially if you aren’t thinking about American-style breakfast or porridge. Sonam said he would come back to pick us up and take us to lunch at his house (above upper market) around 11:30. He had also invited his uncle and aunt, and some other family members.

There followed many deliberations over clothing. I thought that people would be wearing traditional Bhutanese dress and we should follow suit. Zoë was worried about being overdressed, and in fact, I had never seen Sonam in a gho–he was always dressed more casually in his shop. Eventually, we persuaded James to send a text asking about dress. No reply. At about 11:20, we all put on Bhutanese clothes. At about 12:15, James called to ask more directly. Sonam was on his way down, but his wife said to just wear normal clothes. Everyone else shifted into civvies. I said I wanted to wait and see what Sonam was wearing: two minutes later, he arrived wearing a gho. Everyone else shifted back into Bhutanese dress, while Sonam went to get something from his other house. Of course, when we arrived at his house, most of the teenagers and children were wearing t-shirts and trousers, so Zoë felt overdressed.

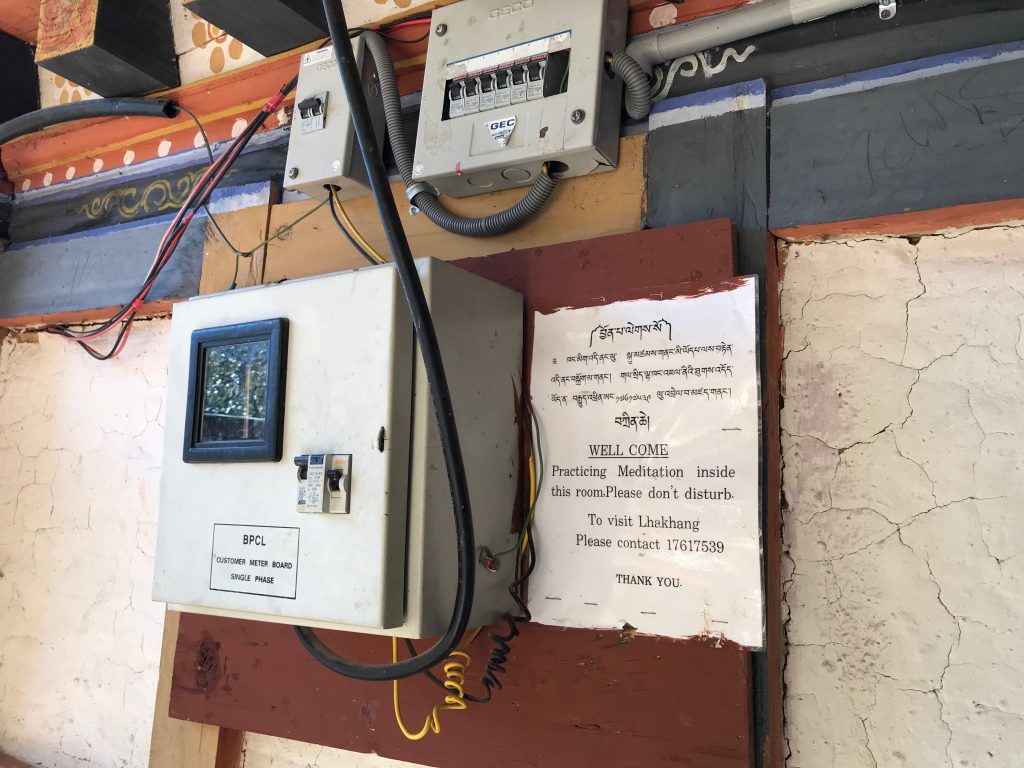

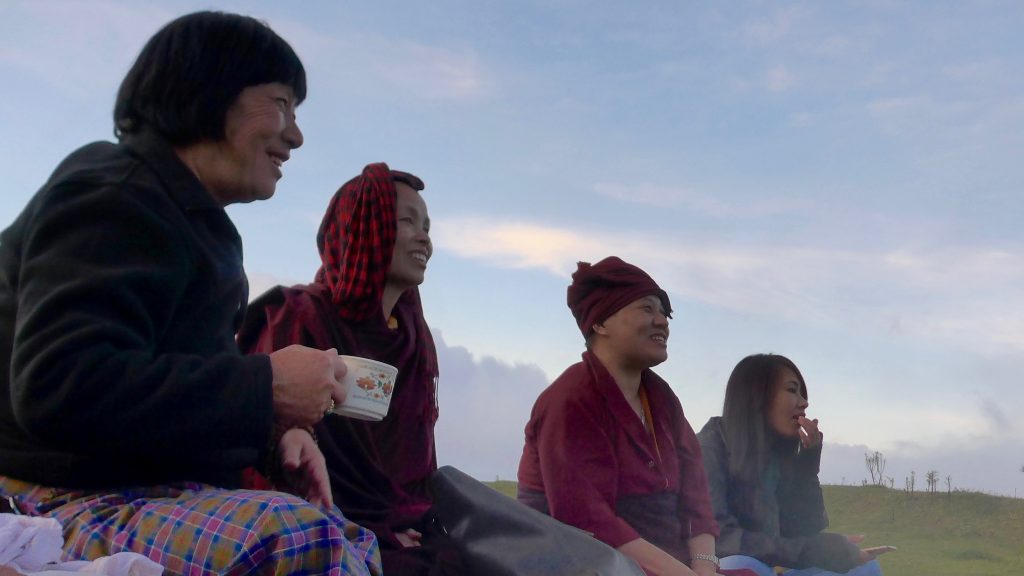

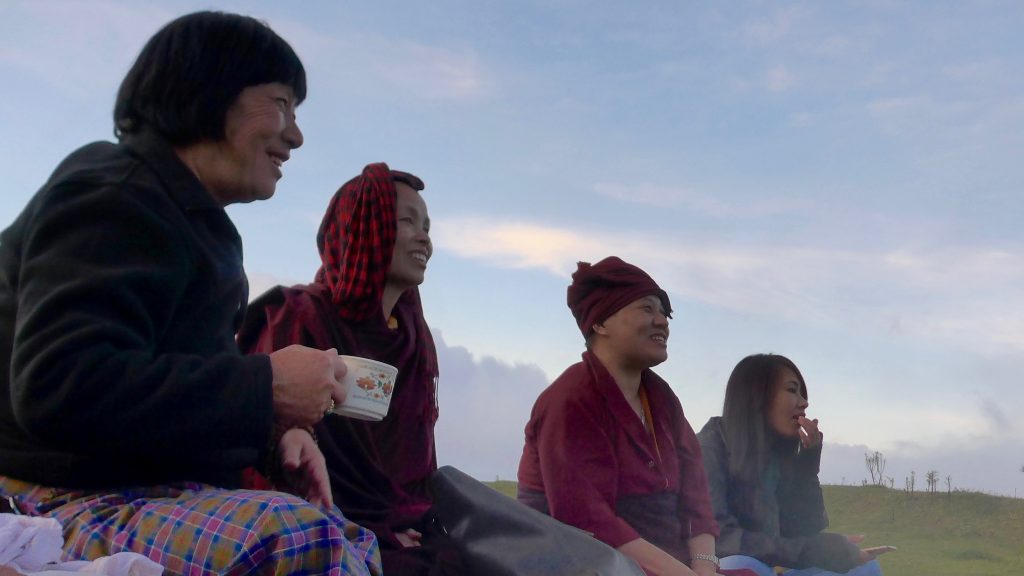

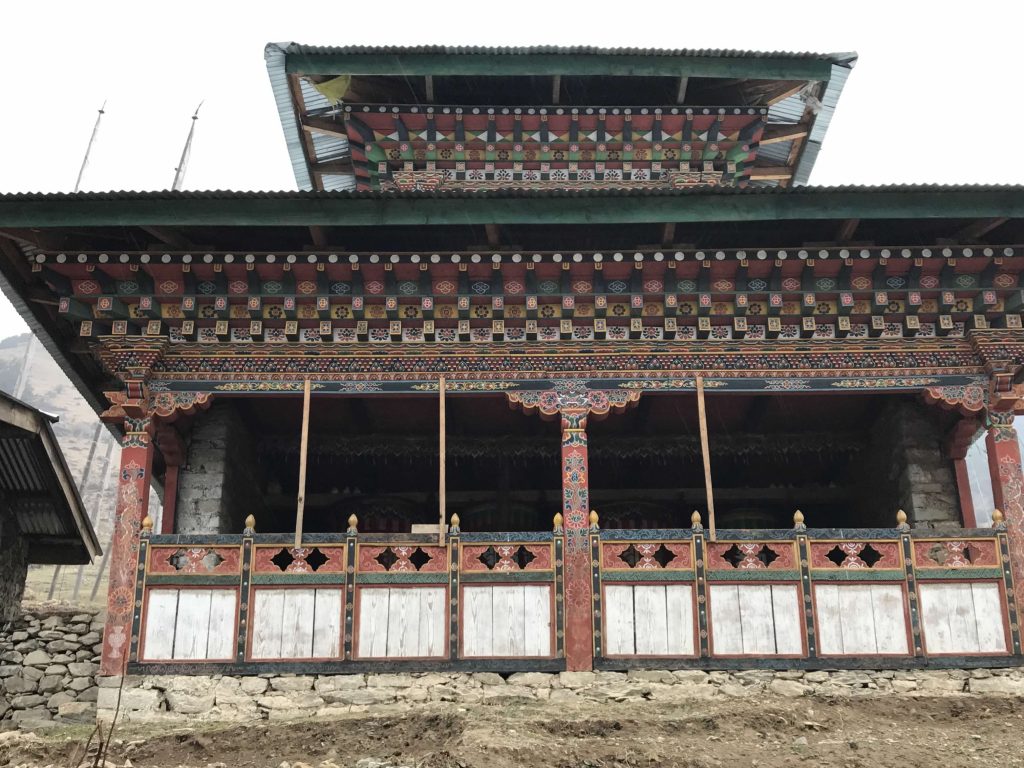

The rain had stopped by this point, and the sun was struggling through, so we didn’t actually go to the house–instead, we climbed some stairs to a grassy plateau above the house. There was a small prayer hall and a roofed table there; mats were spread on the ground for sitting, and there was a special seat of honor for the chilips (foreigners), made out of a car seat bolted to a wooden frame.

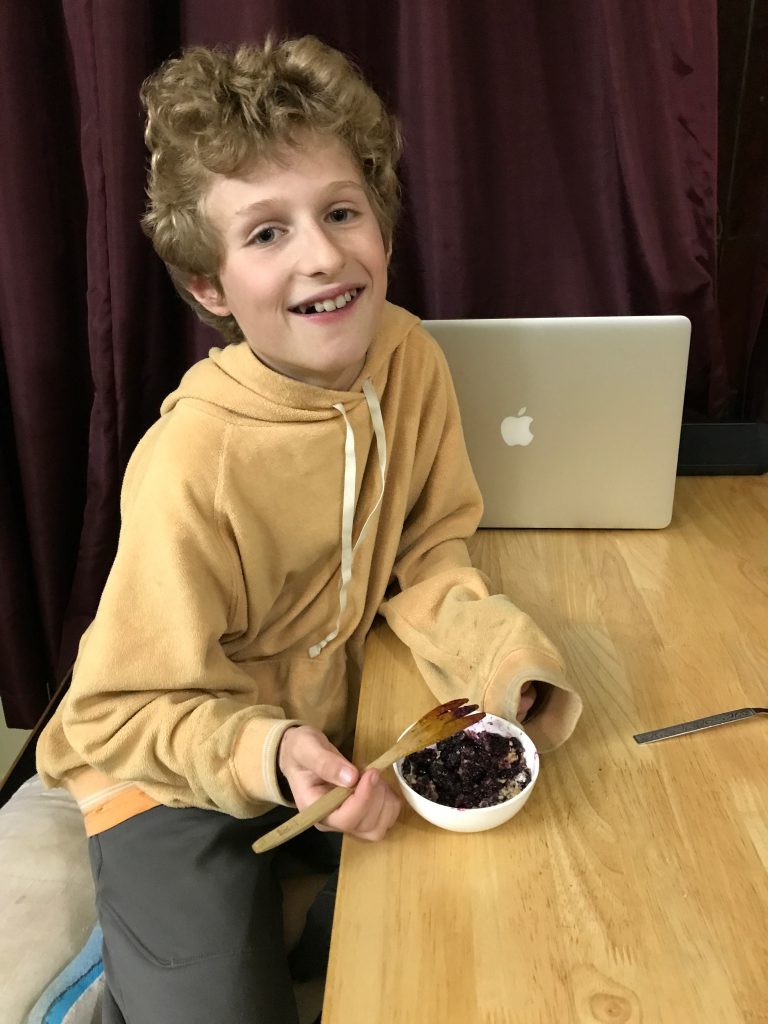

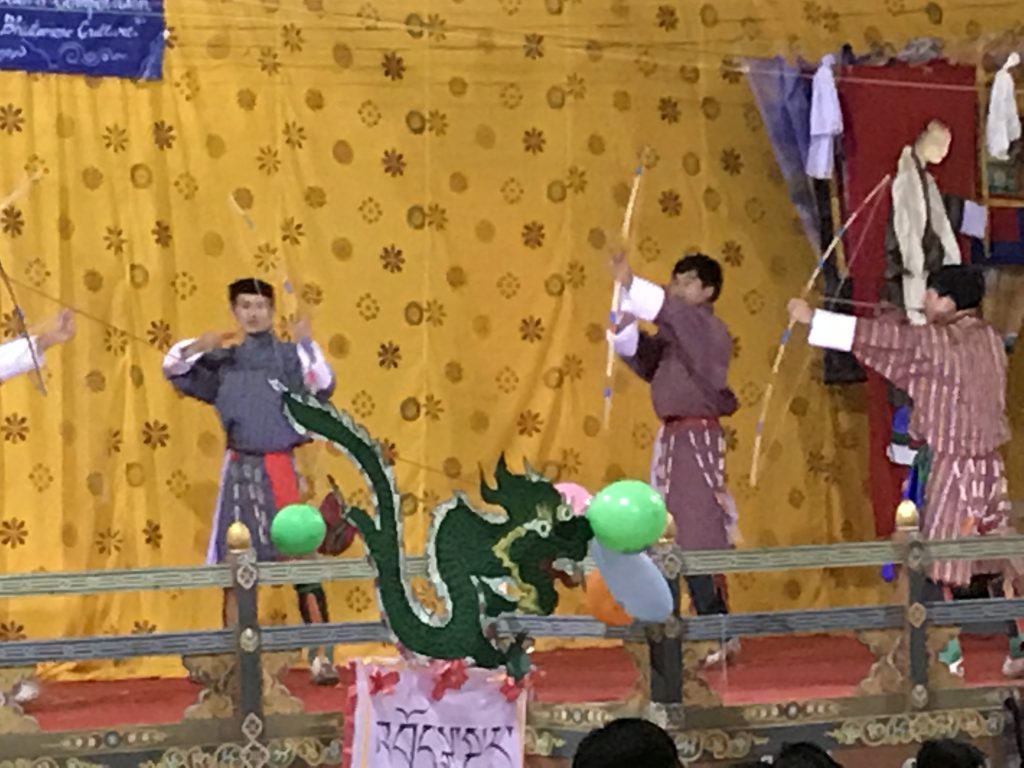

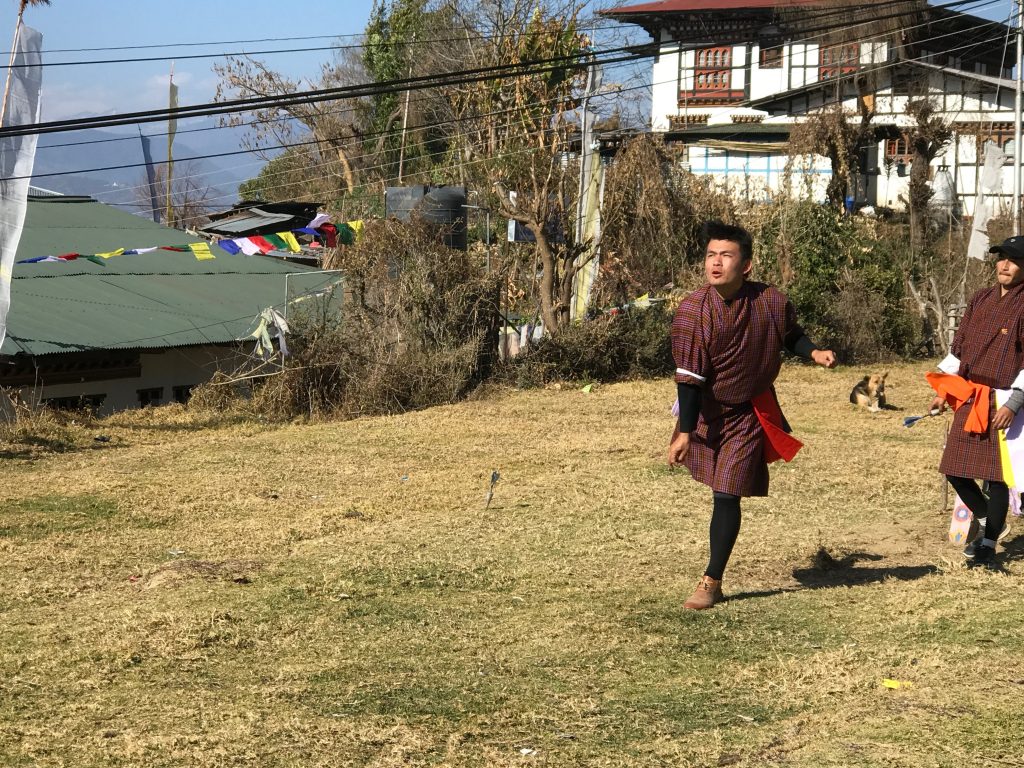

The meal began with suja (butter tea): I tried to warn Sonam and his wife that we could only drink a little, and this led to us being given half-full mugs instead of full mugs. “In our tradition, it is a good omen to drink a mug full to the very brim,” Sonam explained. “Oh, is it a bad omen for us to take less?” I asked. “No, no, it’s fine–but if we are in an archery tournament, we take a full mug, and if we cannot drink it all, we just set it aside.” Good to know, especially for our next participation in an archery tournament. Jeremy refused to take a mug at all; I was again the only one to finish mine. The memory of rancid yak butter tea is always with me, making Bhutanese suja much easier to swallow. Jeremy ate a lot of cookies to compensate for not drinking suja.

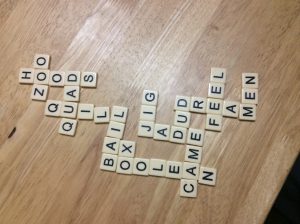

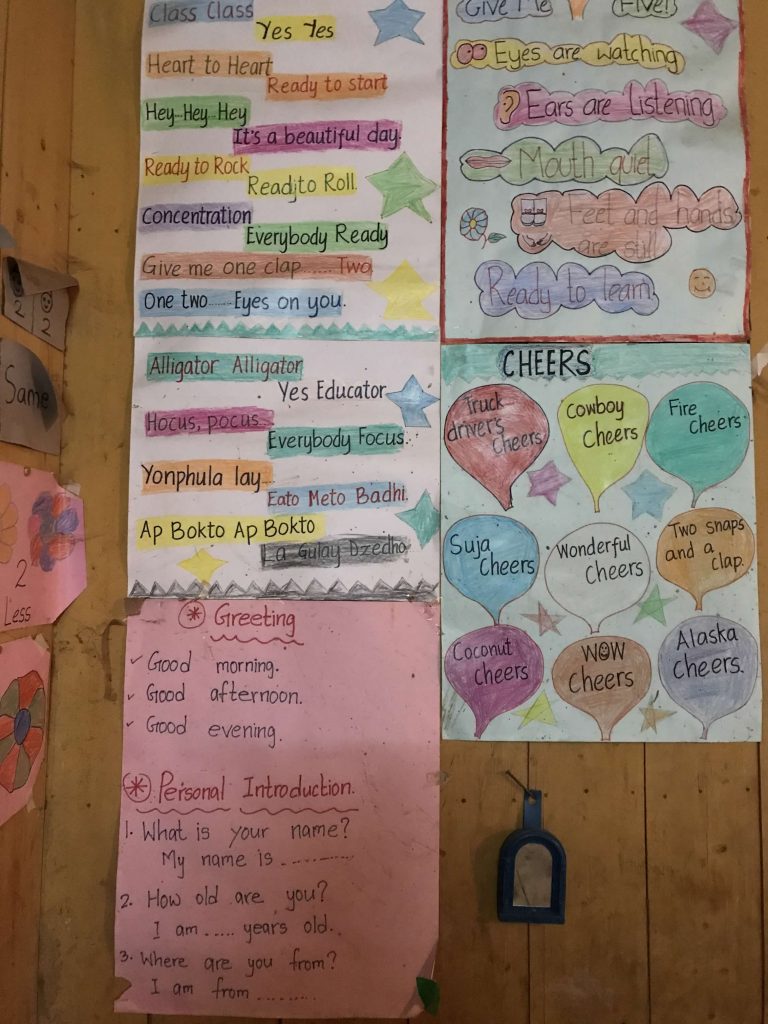

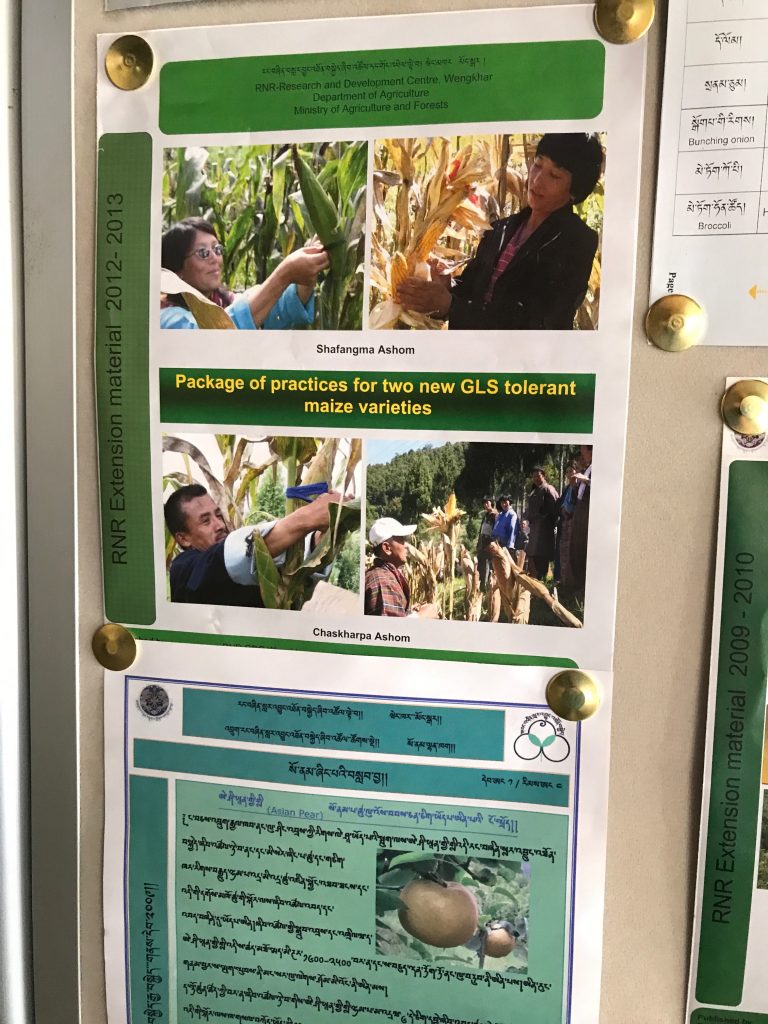

After suja came arra. Sonam had wanted to show us the traditional container, but he had forgotten to bring it. The arra was very mild, vaguely reminiscent of sake to me, which made me think it was made from rice. But no–maize is the basis. Maize is mixed with yeast (explaining, perhaps, the large size of yeast containers available in the market), and then left to ferment for about a month. The mash is put in one container, with another bowl as a lid, and another smaller container inside to capture the condensate. “Ah, so it is distilled?” asked James, and Sonam confirmed. “Very strong, then,” James noted–but it didn’t taste especially strong to me. To go with the arra, we were given spicy Indian-style nibbles.

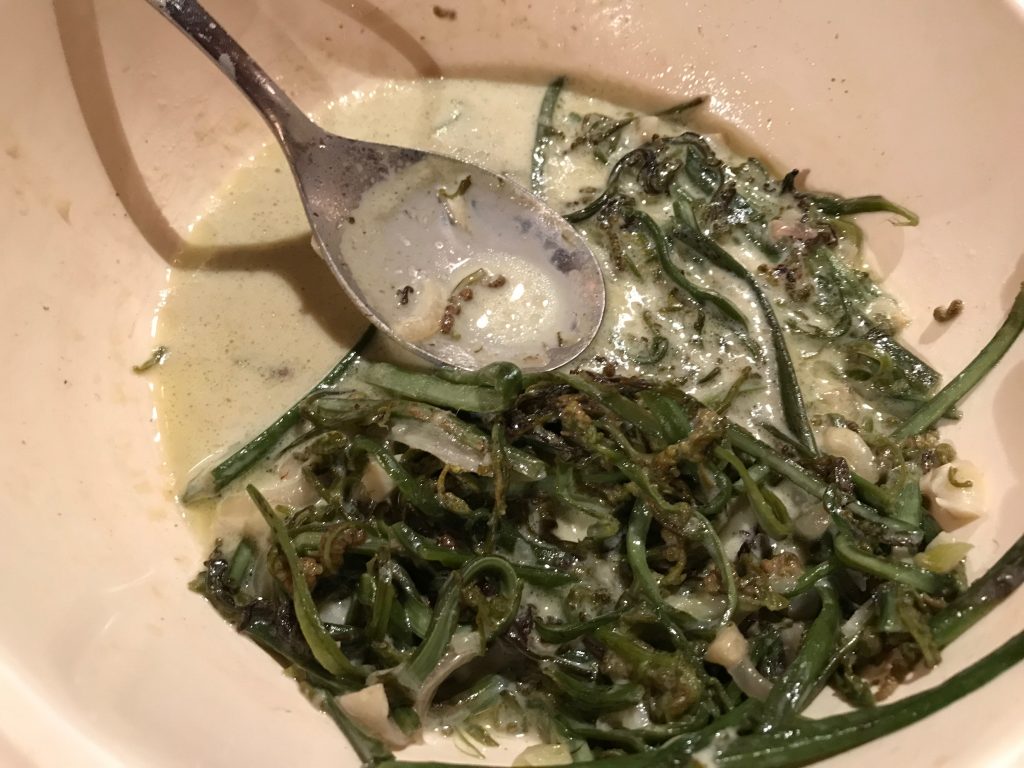

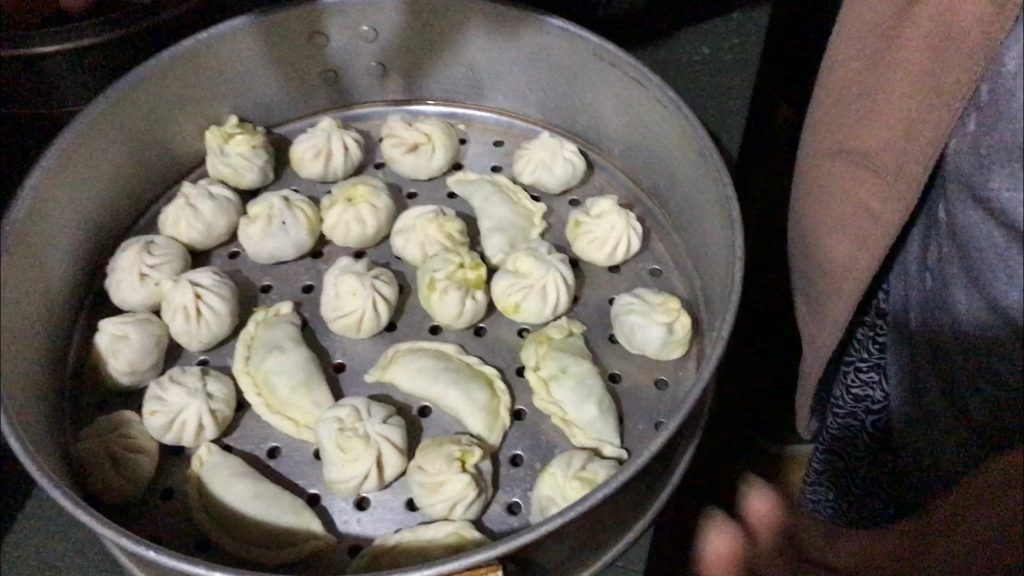

Then came the feast. We should have finished our arra before the food, but Sonam’s wife noted that Westerners often take wine with their food, so we were granted an exception to the rule. Two kinds of rice, many kinds of meat dishes, one paneer dish (perhaps for the nuns present?), two kinds of ema datse, beans.

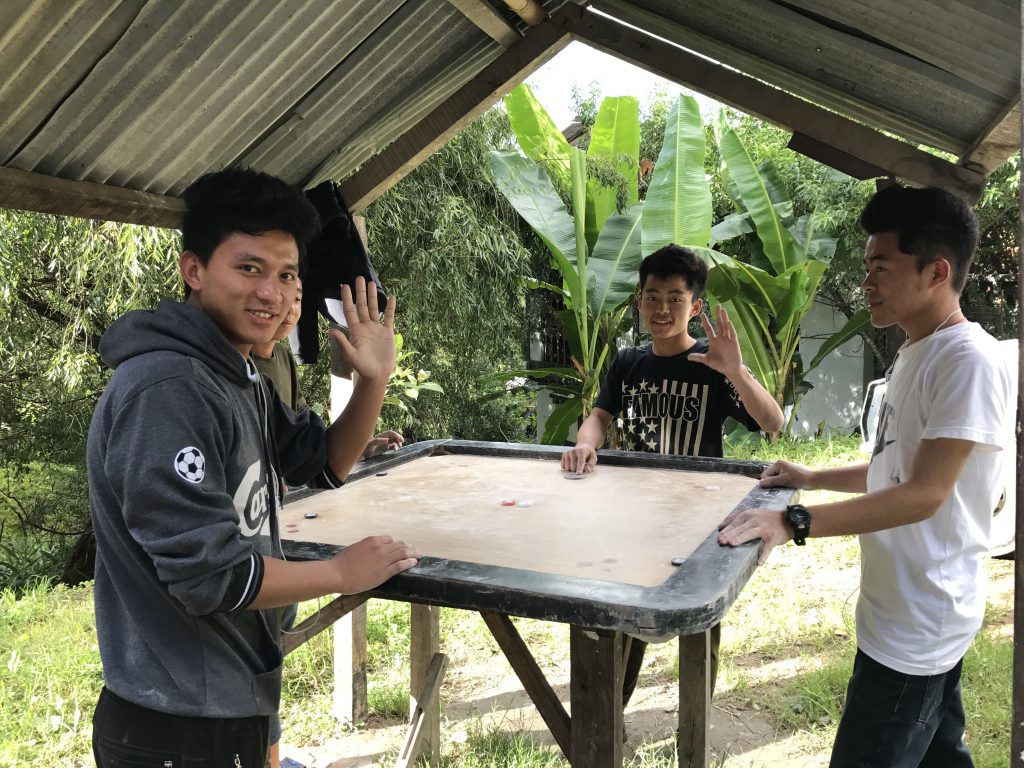

The group had split in three: the older generation, the chilips (foreigners) with Sonam, and the younger generation. We went over to the kids’ mat for James and Jeremy to do some card tricks—Sonam did one too–and then it was time for dancing.

Sonam had to work hard to get the dancing going, but eventually there was a small circle of dancers (mostly the older generation). Sonam and his uncle were the most graceful (in my view). Gracefulness is the key. Sonam said he could dance Bhutanese-style, Nepali-style, Hindi-style. I asked whether Nepali dance was the same as Bhutanese, and he said it was more energetic. “Quite tough.” Eventually James and I did a little swing dance to Bhutanese music, in the interests of cultural exchange. Sonam’s sister-in-law was taking photos and videos and Sonam said he would share them with us. I’ll try to post a link if anything comes through.

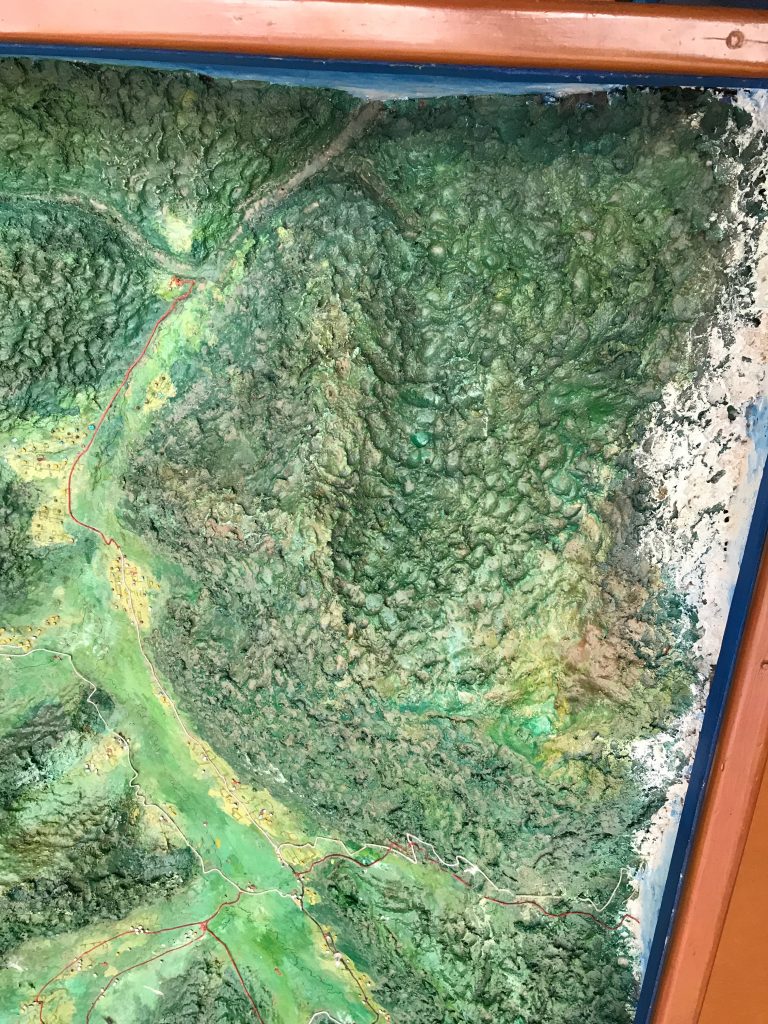

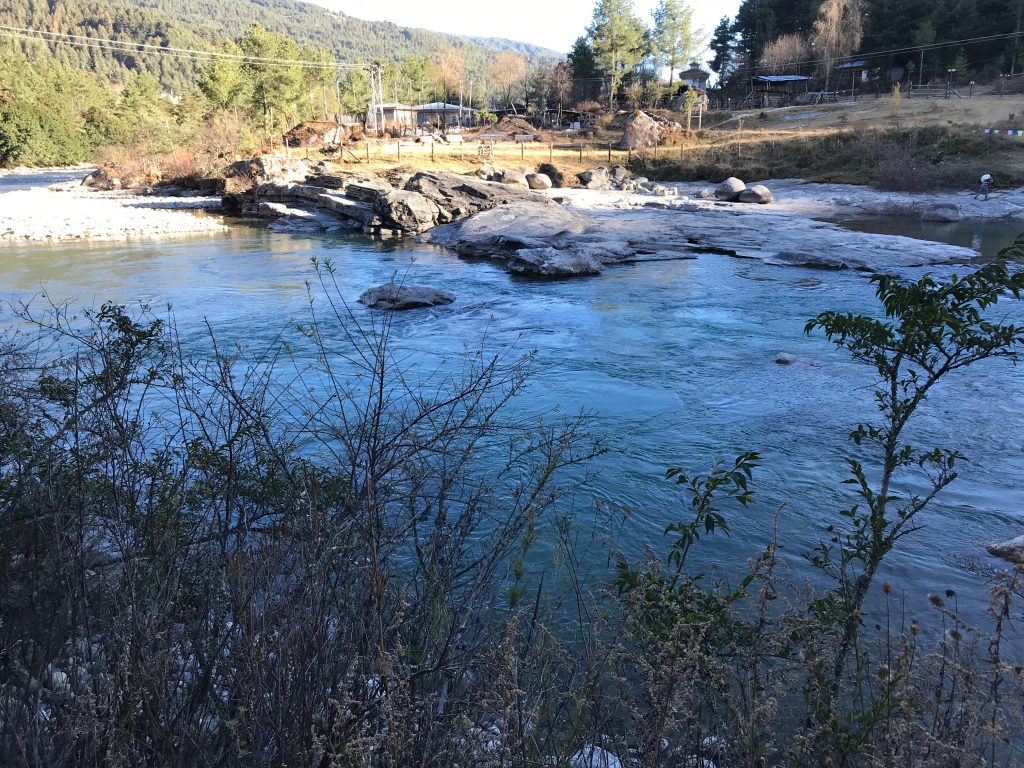

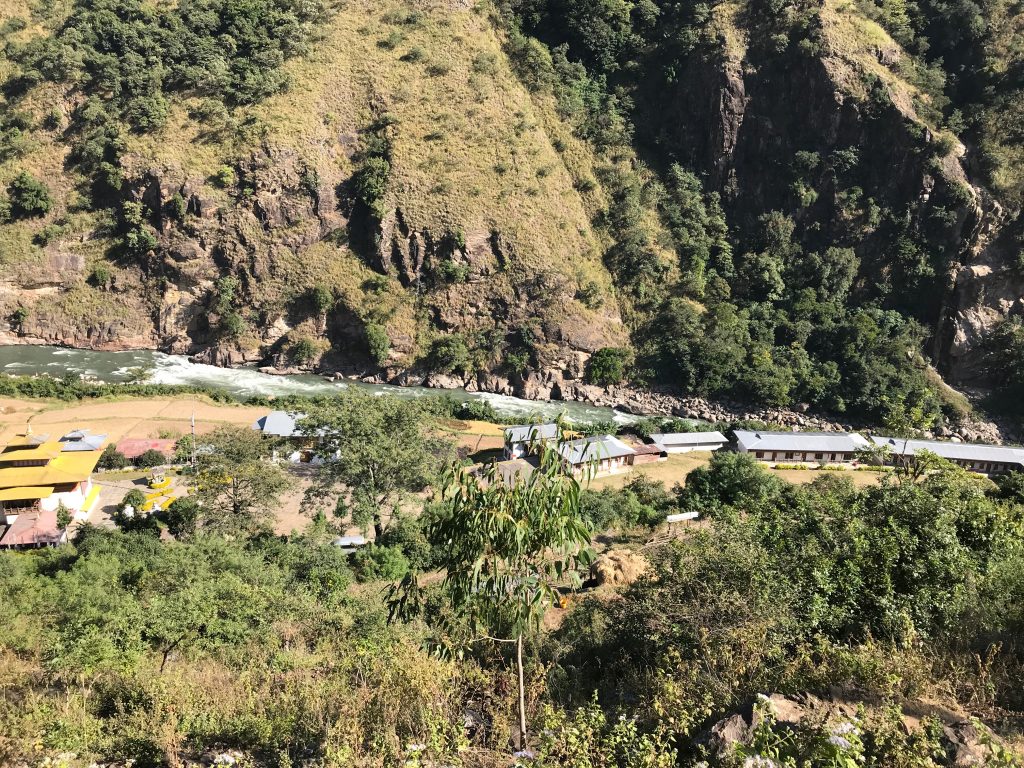

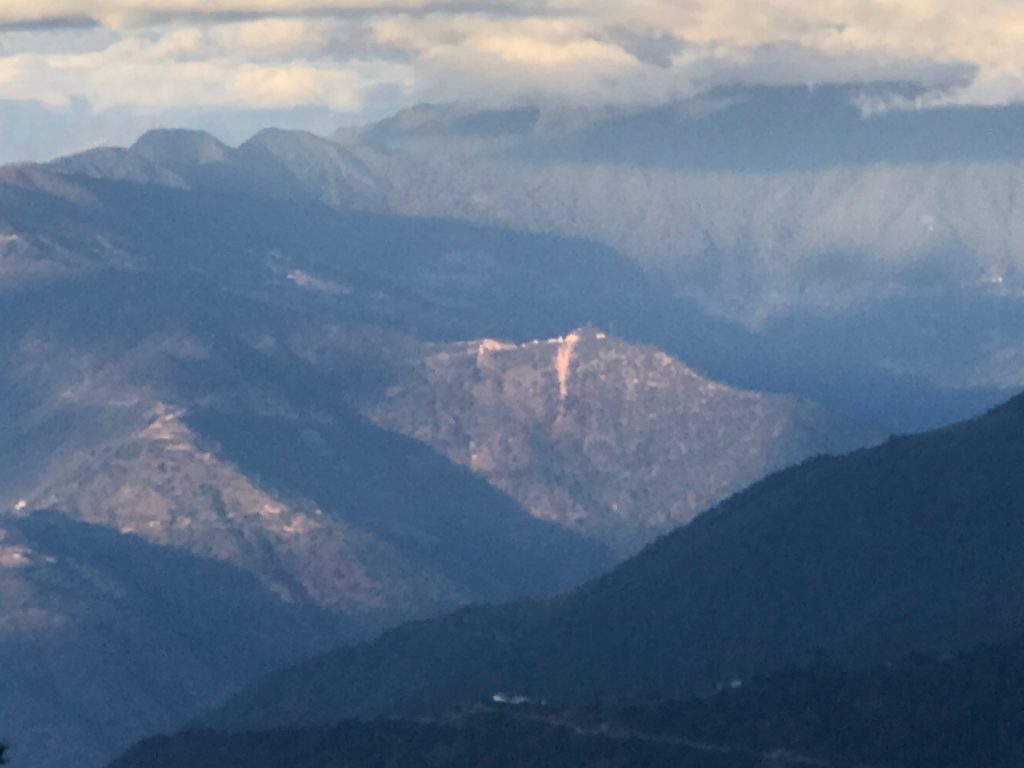

Then we (translation: women and children, not the chilips) packed up the picnic in order to go up to Yonphula. I asked Sonam if we could go and change, and he drove us back down to the guesthouse for a quick change, complete with a peek out over the lookout. Sonam told us the name of the river–Drangme Chhu–the longest river in Bhutan, and also identified some of the towns on the other sides of the valley, in neighboring Mongar.

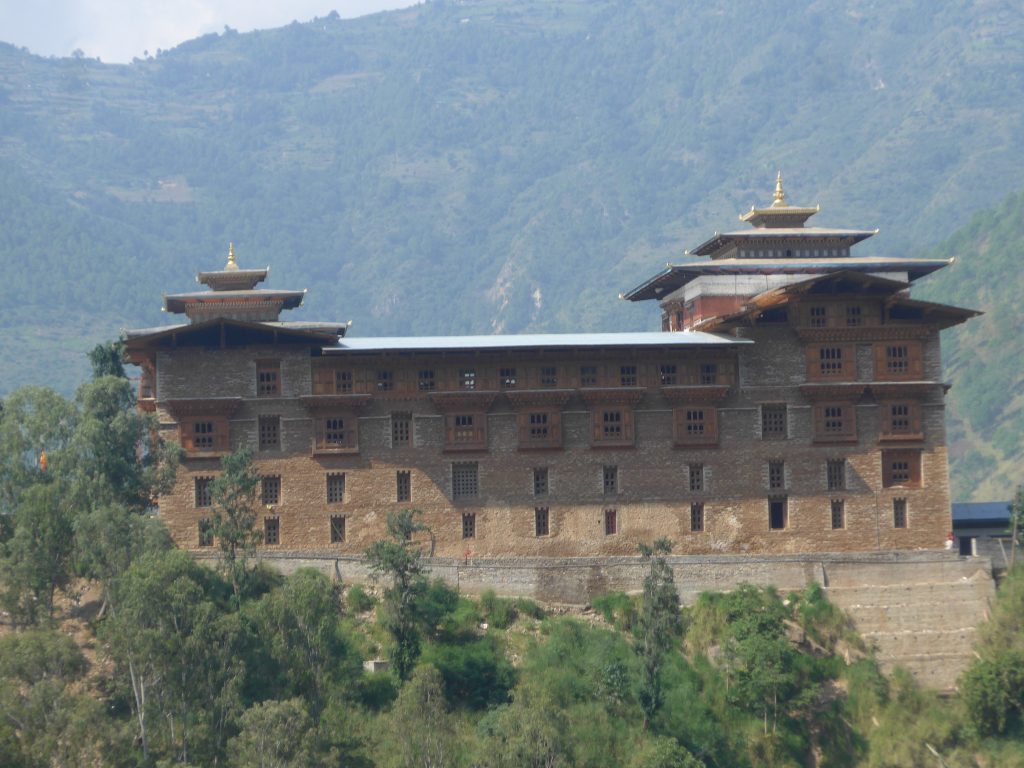

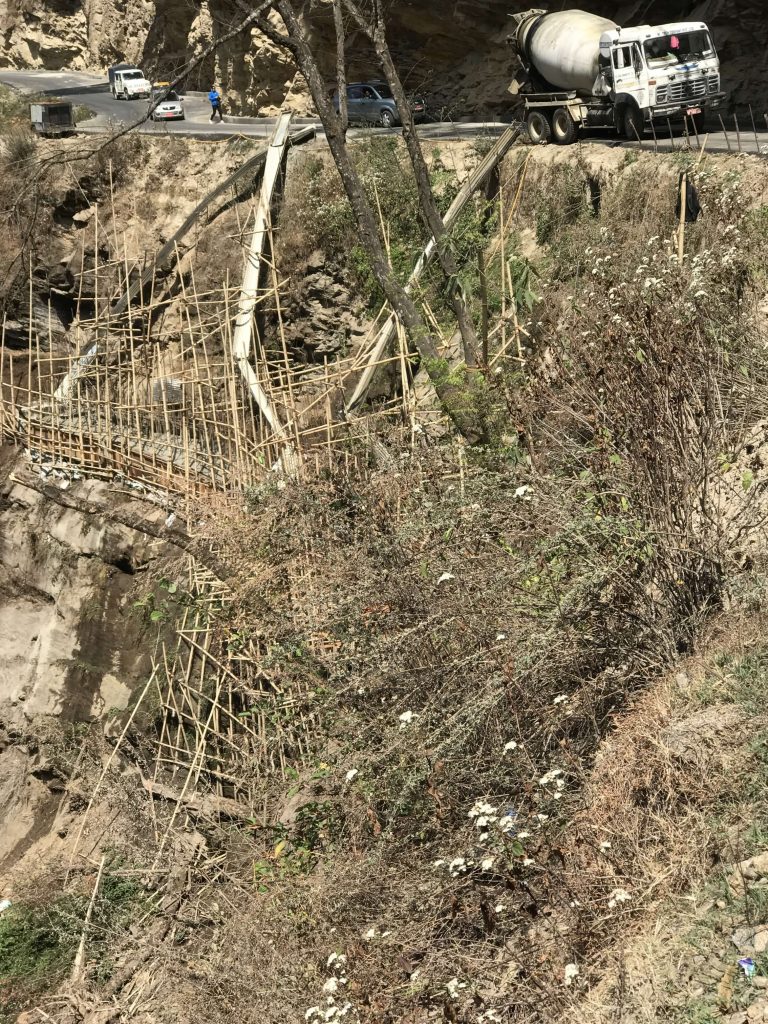

Sonam’s uncle was a new driver, so we drove carefully up the mountain behind him. We stopped briefly by the road to the Kelki school construction to look out over Sonam’s birthplace. The house is now occupied by someone who is tending the fields, keeping the farm going. The roof visible from the road belongs to Sonam’s mother’s eldest sister; then there is a house belonging to the middle sister. Sonam’s mother, as the youngest sister, has the house at the very bottom of the set.

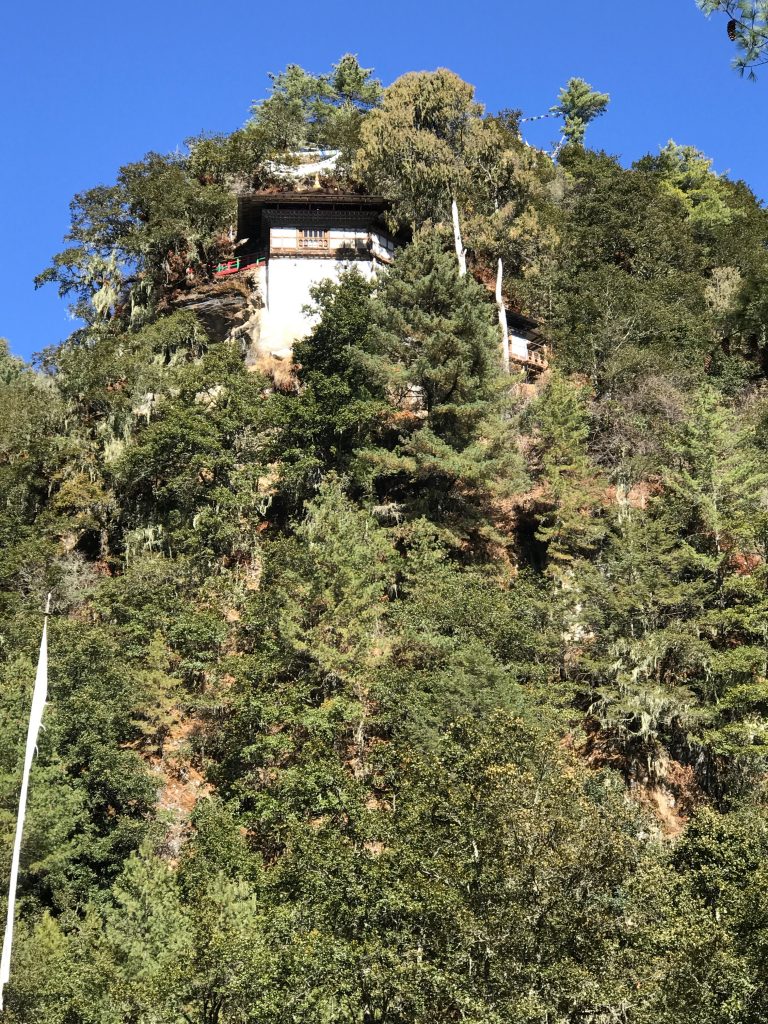

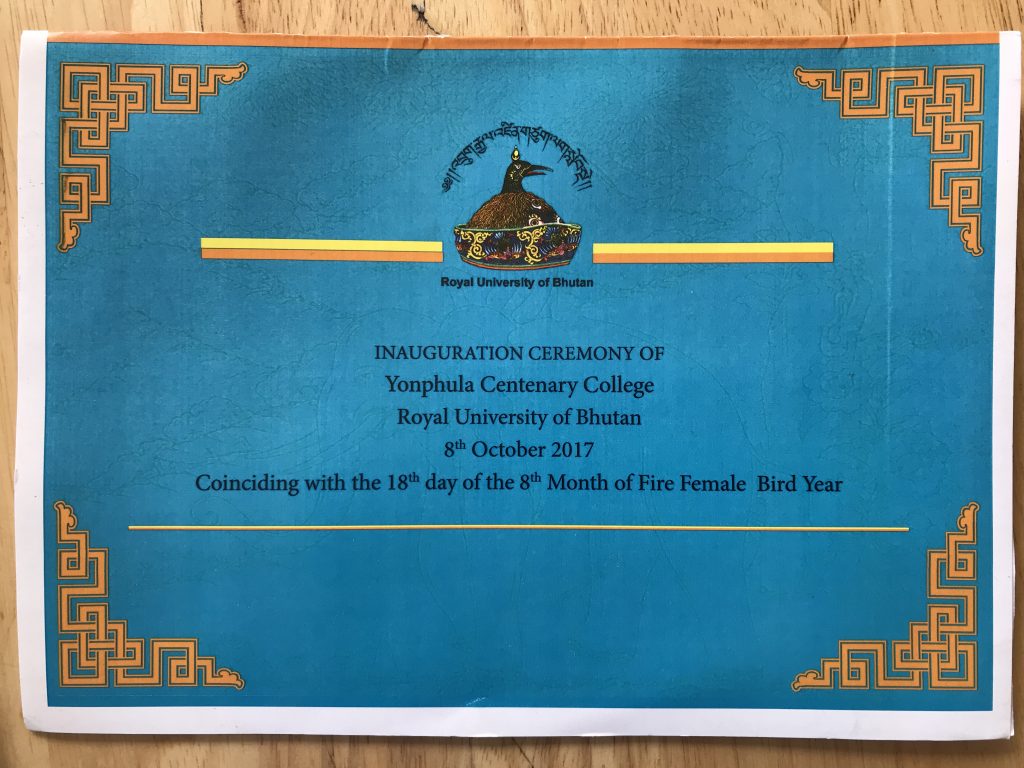

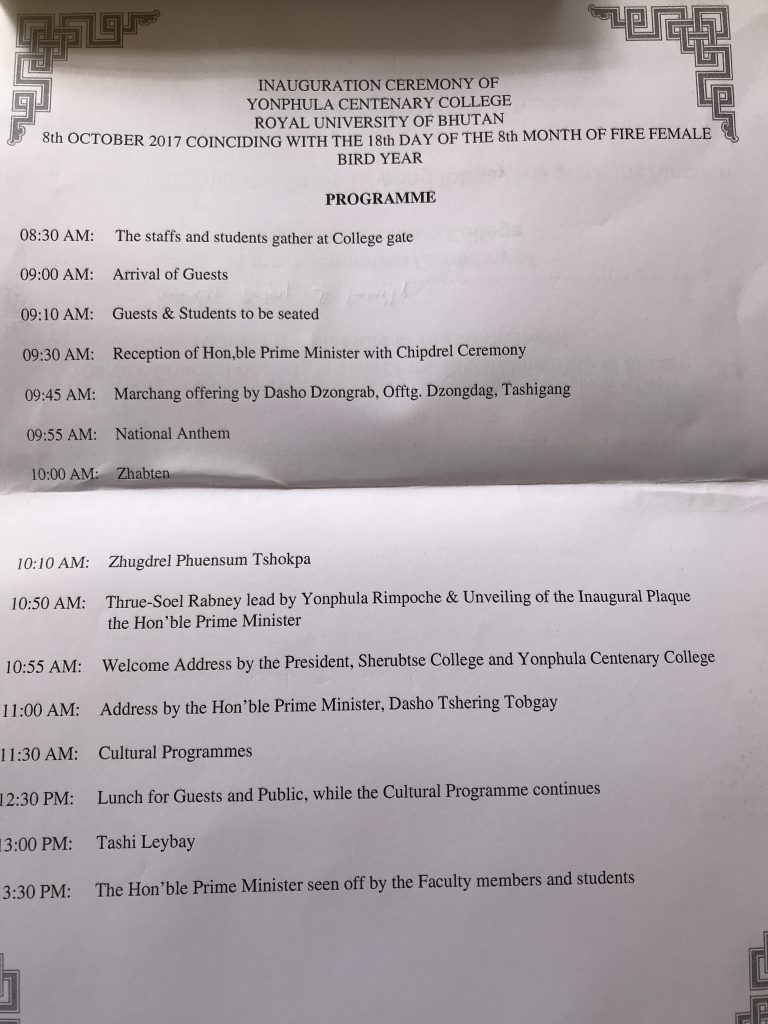

Everyone was going to Yonphula yesterday: we drove through the Indian military base up to the air strip, where people were driving through the fog, parking to climb the hill of displaced soil at the end of the runway, picnicking on the runway itself,

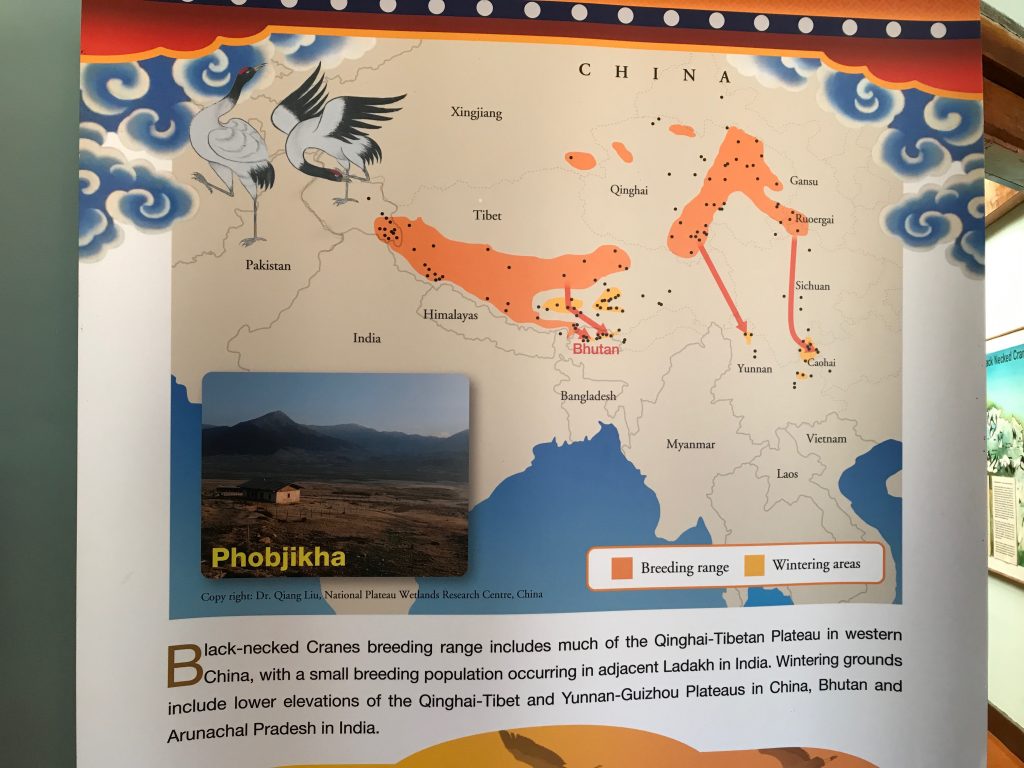

or parking to look at one of the magical lakes on the side of the mountain. Unfortunately, the construction has muddied the lake, which would normally be a turquoise color.

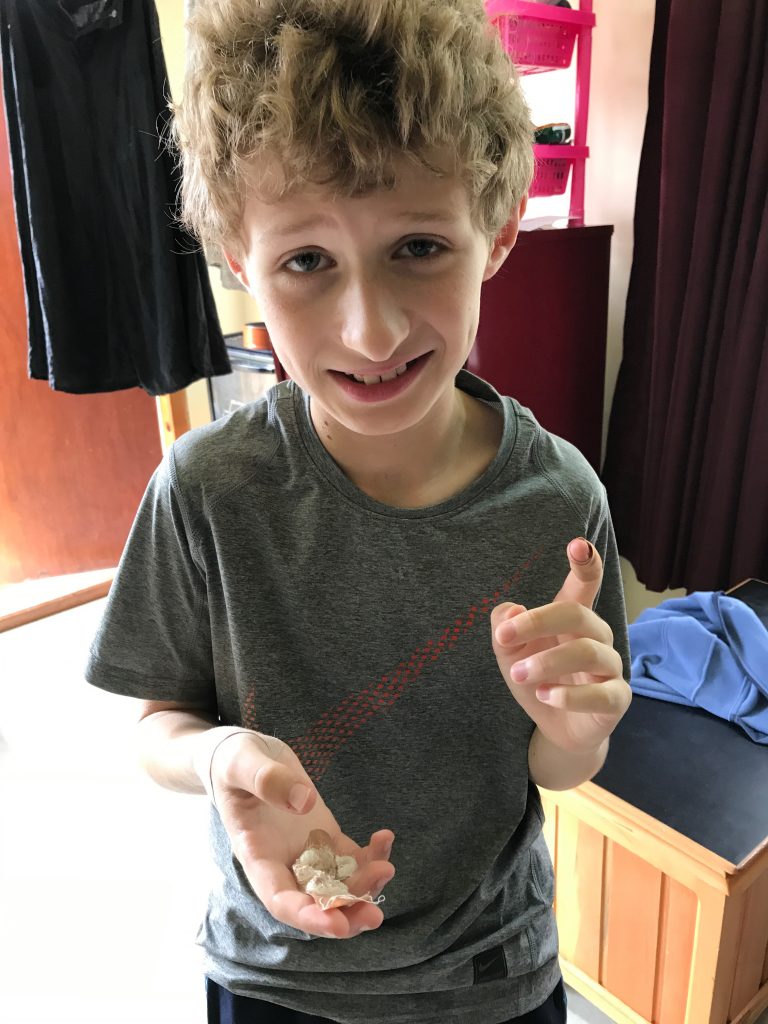

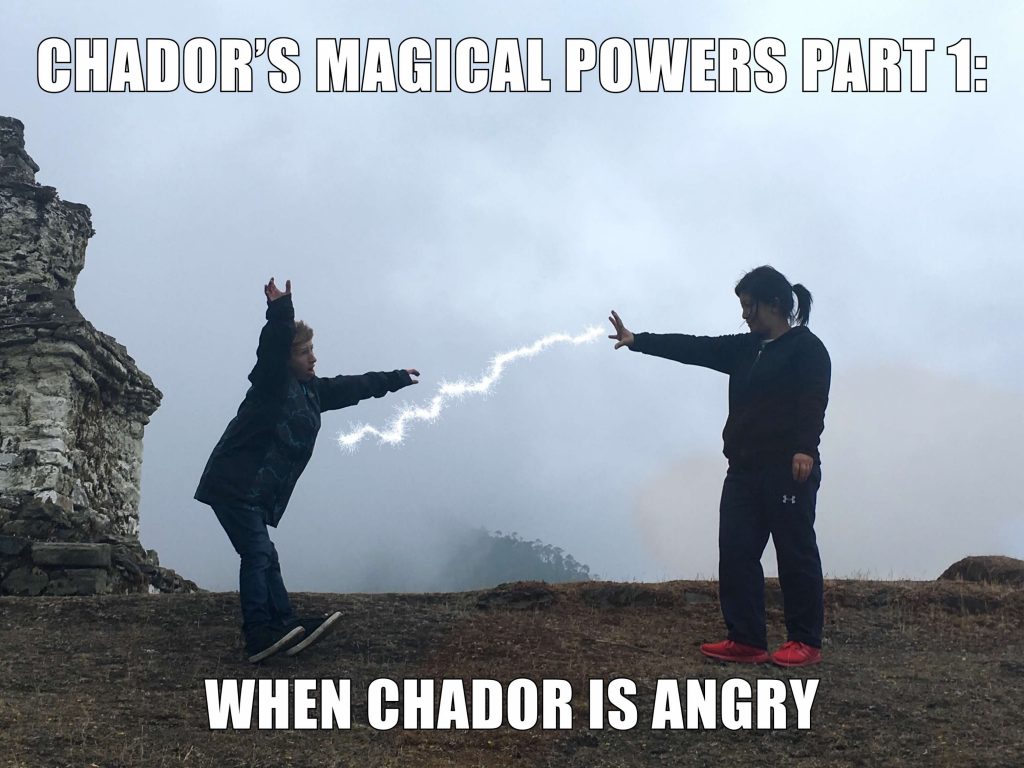

“We believe the lake is inhabited by a mermaid,” said Sonam: I imagine this was his translation for naga, usually a female spirit of rivers or lakes. “Cool!” said Jeremy, who promptly started climbing down the scree slope toward the lake. Sonam followed him good-naturedly, and I went too. In the meadow below the scree, Sonam, quite the photographer, took a bunch of photos. Jeremy tried to slide down closer to the lake, but Sonam stopped him. “It is very deep!” he said. “Don’t go closer.”

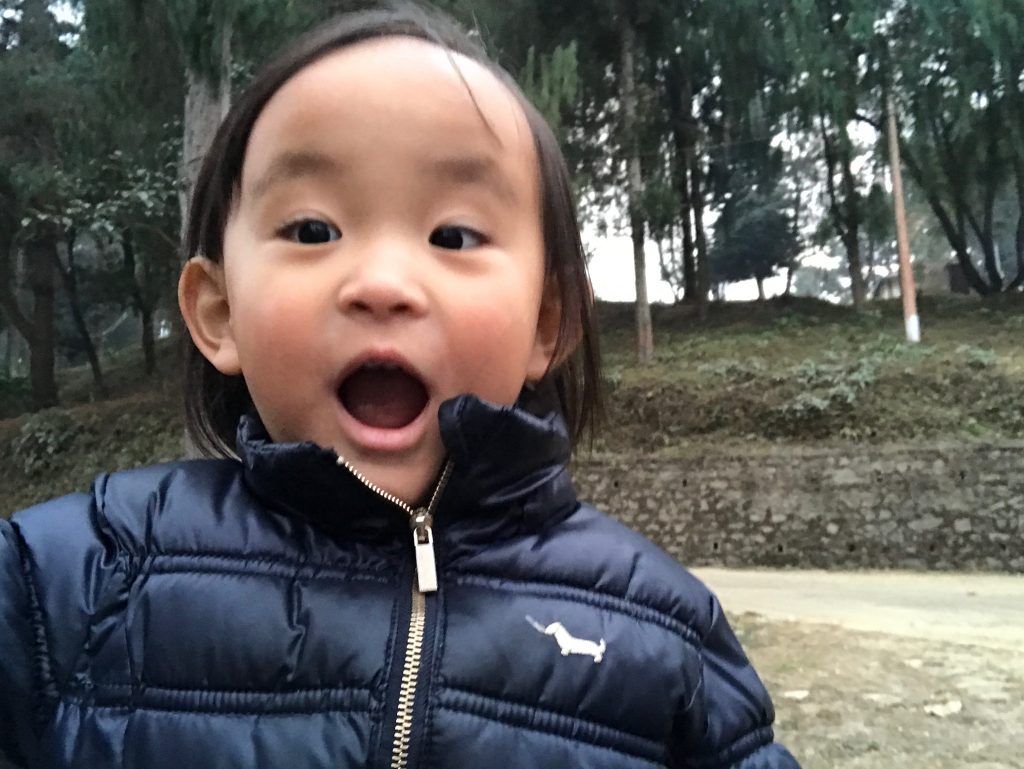

By the time we turned to go back up the hill, Sonam’s children and wife were on their way down to us. Jigme Norbu Wangma, their six-year-old, slid down to Jeremy and his mother stopped him sharply. “We believe if you go in the lake, she will not let you go again,” she said, referring (I think) to the naga. This idea caught Jeremy’s attention much more firmly than any worries about depth.

Sonam’s wife Dechen showed us how to pick the last blossoms from my favorite green-headed plant and make little rings from those blossoms.

We walked toward the overlook at the end of the lake as the fog blew in–then it was time to climb back up the scree to those waiting patiently at the airstrip for our return.

At the top, we met Thobsten, our neighbor from the guest house with Tshering Thinley and his daughter (her face always buried in her father’s shoulder). A small world. Then the children started to walk down the hill to our picnic site while the grown-ups drove.

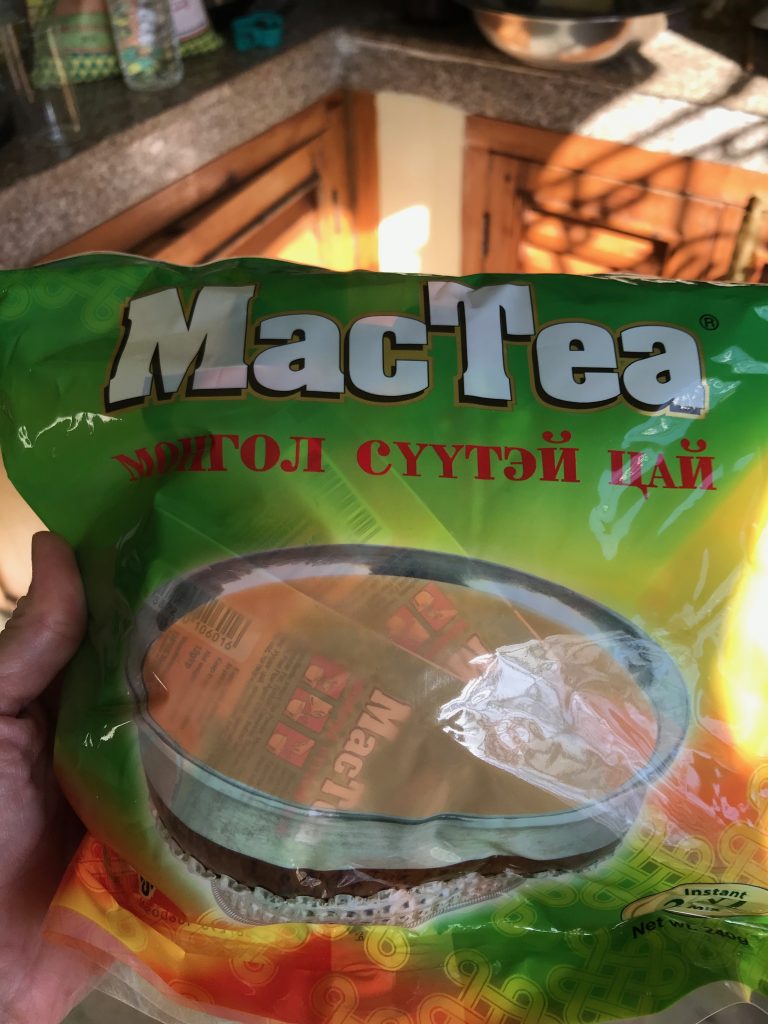

We set out mats and Sonam’s sister-in-law served everyone sweet tea, coffee, and eggy arra.

“Eggnog!” James announced. You half-scramble an egg and then pour in arra. That’s as much of the recipe as I could follow. It was warm, distinctly stronger than the earlier arra, and very unusual by Western standards (I had to finish James’s cup).

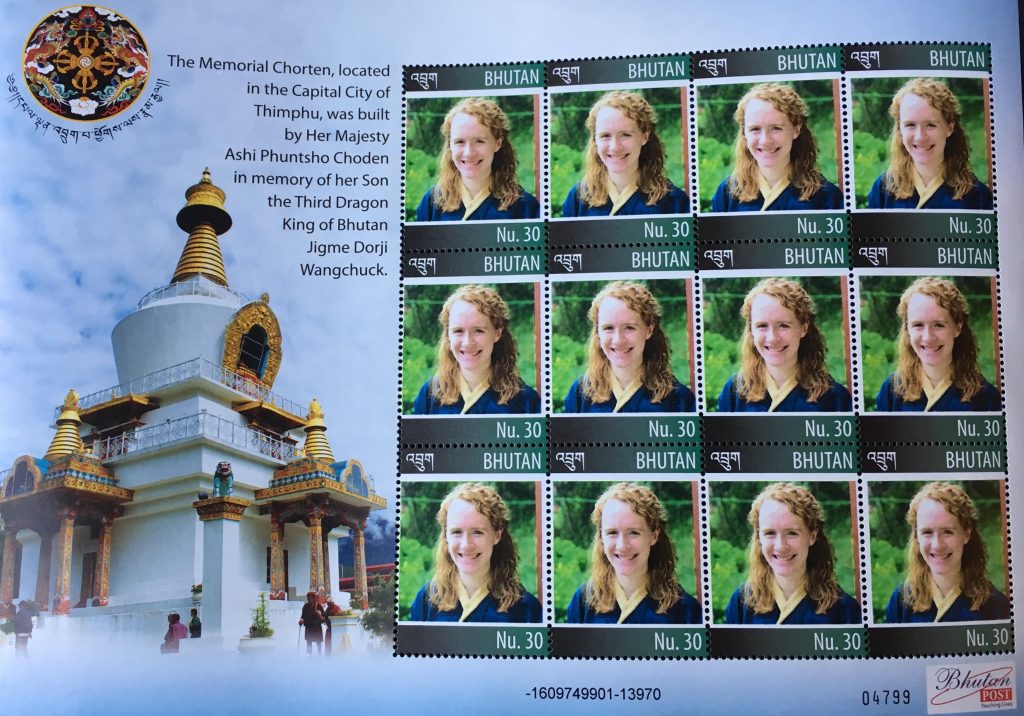

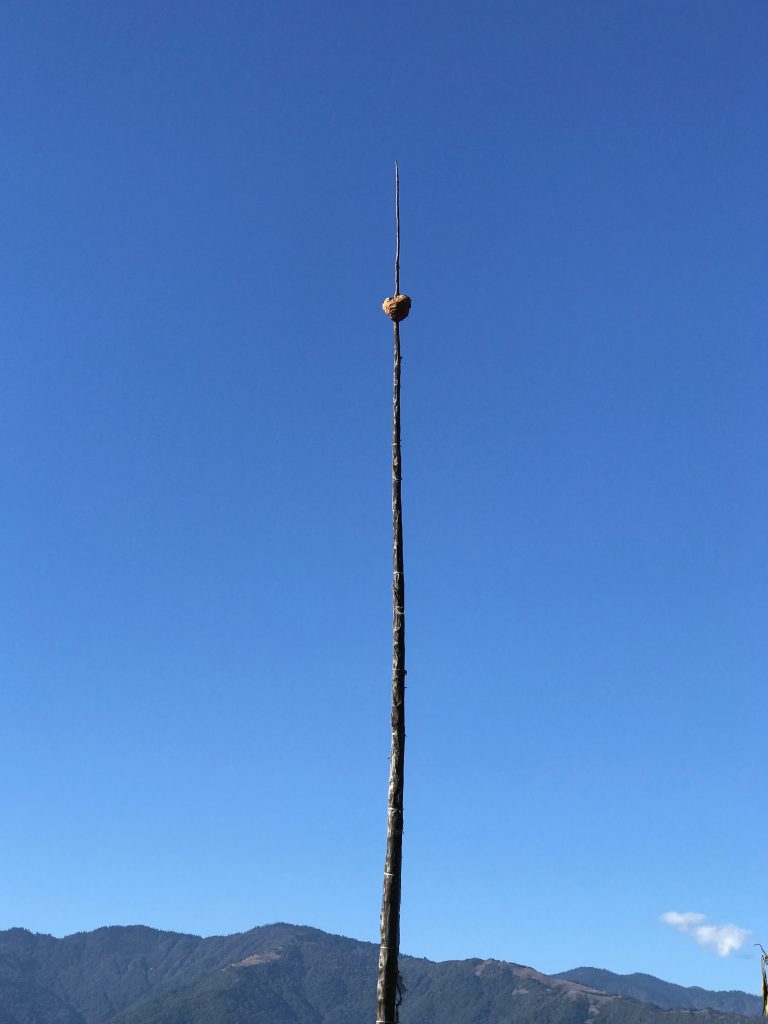

Sonam maintains the traditional practice of carrying an antique drinking cup with him. He inherited this from his aunt, and older people would always carried one in the “Bhutanese pocket” formed by the front of their gho or full kira.

The inside is silver; the outside a beautiful wood burl, turned on a traditional lathe:

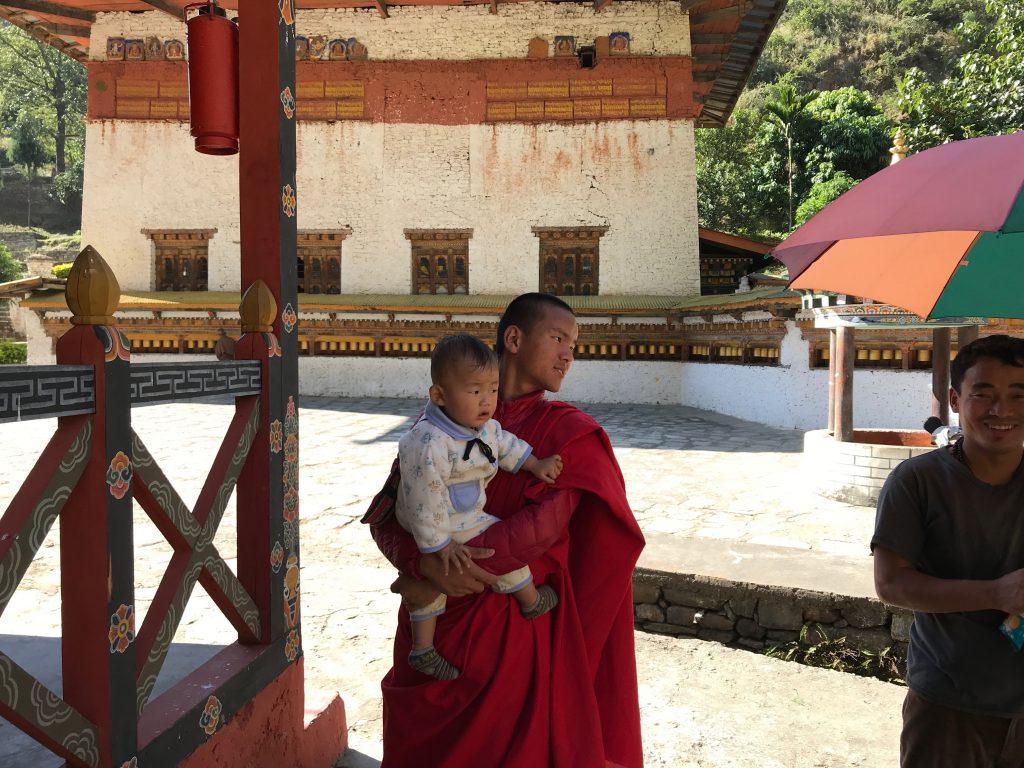

As we sat and talked and drank and listened to music, other cars passed by, returning to Kanglung from the mountain top. A truck full of monks passed by,

as well as another truck full of a large family.

“Hello, Jeremy!” called Kaka, passing by in the back of another truck. Chencho and friends drove by also. It felt as if everyone we knew was up at Yonphula.

Jeremy played Connect-Four with Sonam and Jigme Norbu:

The music speaker had been brought up the mountain, and eventually a microphone appeared, introducing karaoke. With much laughter and many demurrals, the mic was passed around the circle, and everyone expected to sing something. Pema Dendun, Sonam’s 9th grade son, was the star of the show, with an amazing voice and great command of American pop lyrics. Dendun started us off, and after his younger siblings practiced on an American song, he sang again to show how it was really done. Sonam too had a beautiful voice and he sang a traditional song. (I’ll post a link to a video in a while.)

His aunt sang a song about a peacock landing, which Sonam said referred to us (human beings? this party of picnickers?): “It is very traditional and very meaningful.” As dusk fell over the Indian military base, we began to pack up.

“It is our tradition,” said Sonam, “to close with thanksgiving.” There was some struggle, though, to recall the right song and the circle dance to go with it. As the group struggled, some students came leaping down the hill from the airstrip. “The students will help us,” Sonam said, and they came into the circle and led the dance with much more precise footings and gestures. The moves ranged from stepping in and out of the circle, with a hopping kick at the innermost point of the circle, to movement back and forth around the circle, to joining pinkies, to putting arms around each others’ shoulders and swaying and stepping first to one side, then to the other. The song finished, the students waved and continued on their way, and we began carrying mats and thermoses back to the car. Partway down the hill, we passed the students and everyone called greetings. As they fell behind, one female student called, “Goodbye Jeremy!” much to his bemusement. But Jeremy is known wherever he goes.

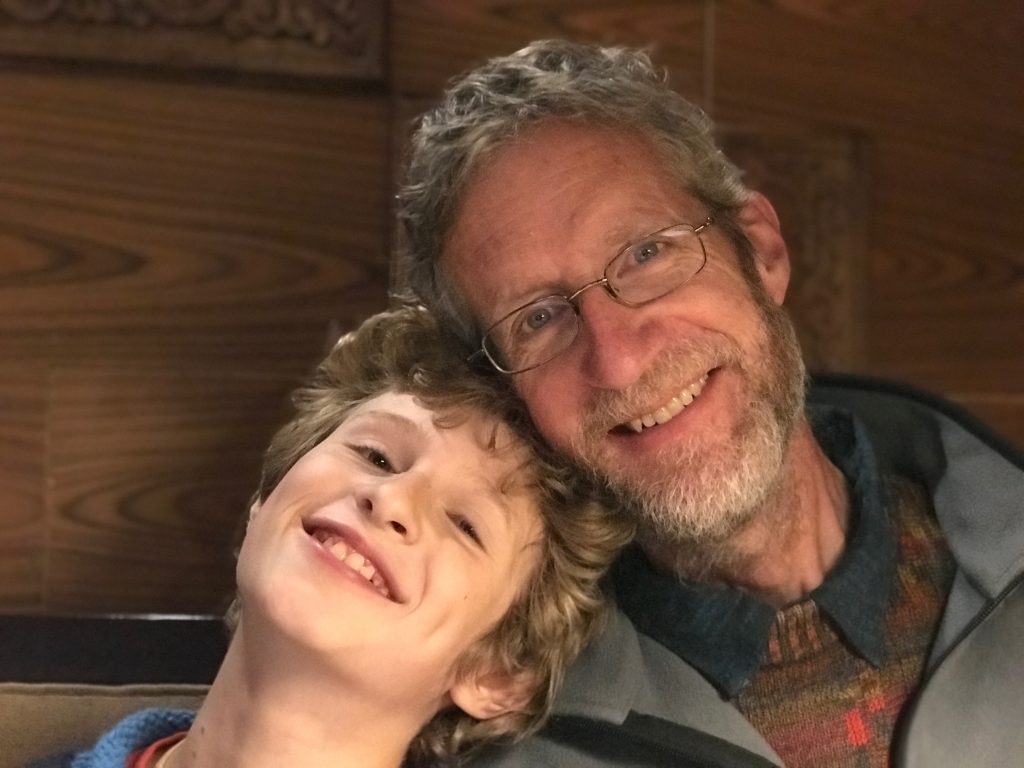

(Simon photo credit)

(Simon photo credit)